In a three-part article, Rūta Žemčugovaitė reflects on Flourish! the Learning Journey designed by One Resilient Earth that she joined in September 2022. She also highlights the influence of the Learning Journey on her artistic practice. This second part of the article addresses how she recovered meaning through a conversation with Bayo Akomolafe.

In the first article of this series about Flourish! experience and my personal creative journey, I wrote about the vulnerability of asking a hard question and how transformative it can be. In the part two (you are here), I share a question that has opened a new trajectory in my art project, called Refusal to Heal, a mycelium sculpture.

For the past year, I’ve been working on a large-scale fungi-mycelium sculpture. Working with mycelium as a co-artist of the project has been quite challenging. Those who work with fungi know that these species have their own timing, and that patience is an insurmountable part of the process. So many times I have experienced disappointment and frustration, leading to apathy, reminding myself that this is part of the experimentation process, this is part of the iterative art cycle that all creatives go through. This applies even more when we work with the aliveness of other species—slow to cooperate, refusing to cooperate sometimes, in their own right.

At the beginning of 2022, outside of Berlin, I found a laboratory I could start working with fungi. After the initial period of experiments and guidance, in the summer I moved into a studio where I continued testing prototypes, and further succumbing to failed experiments. I’ve spent summer evenings alone in the lab, feeling anxious about my process and lack of progress. The period of travel expanded the momentum gap, everything moved slowly: the chaotic testing period of materials and substrates sapped my initial excitement about the project. Mid-autumn I joined a supportive myco-fabrication community where I could pick up the work where I’d left off. During that time, I set the meaning of the project aside, focusing on making the technical details work first. Forgetting that meaning is the fuel to action, that action becomes a consequence of meaning. And meaning is never found in an isolated echo chamber of our minds.

I am convinced that conversations are places of worlding. In conversations, we can subvert the desire to hide our aliveness and expose it in shared spaces of emergence.

“In the right conversations, we can change inner narratives and attribute new meaning to our suffering. We can eat the fruit and risk exposing the vulnerable seed into the soil.”

In one of the Flourish! learning journey calls I had a chance to ask Bayo Akomolafe a question. The question I could not fully understand myself, the question that seemed weird, alien, and obscure. I felt self-conscious and unnecessary. I didn’t know how this question would seismically shift my perspective of my own entanglement with a need to be well-functioning. I felt my chest warming with the thumping of my heart—I’ve learned that at the edge of vulnerability grows a tree, bearing the sweetest fruit.

Rūta: I feel that my ability to cope with the modern world is slowly disintegrating. I feel a thinning veil between me and the reality of the world: the multi-crisis we are facing, the daily encounters with human and non-human suffering, dying ecosystems, and disappearing species. It is becoming harder to process the brokenness of systems out of my own system. It’s becoming harder to function as a normal and normative part of society. The burnt-out sensitive nervous system cannot regulate the stimuli, nor the heaviness of this time. This alien part of me cannot be socialized back into society. This part of me refuses to heal. No matter what healing modalities I try.

Bayo: “That sentiment you just expressed is deeply theoretically dense. It is generational. And what sentiment am I trying to highlight here?

“I refuse to heal.”

There’s a French visionary that has captured my imagination. He lived as a contemporary of François Tosquelles and Jean Oury—these are visionaries that started the institutional psychotherapy movement, which resisted the asylum and its politics during the Nazi occupation of France. In post-Second World War France, this man, I’m speaking of, Fernand Deligny. You might have heard of him, an educator or maybe an anti-educator because he was against <laughs> coddling children. This was a time when about 45,000 people died in the asylum. And not just due to the war or starvation, but also due speculatively, allegedly to the efforts of the Nazi occupation to kill off and discard people that were deemed inadequate, like the people suffering in the asylum, right? So lots of people died. And this is when that movement started to form. Delini was of the opinion that autistic children were not less of, right?

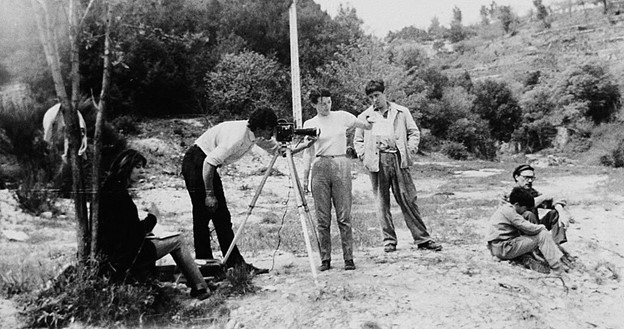

They were not to be healed. There was something powerful about them. And I say this as a father of an autistic son, right? And this is what draws me into his politics. He’s dead. He died in 1996, but he’s not as popular. He’s quite esoteric, but his movement is really catching on, I believe for those who are introducing themselves to his work. He decided to, to leave the asylum and to start these guerrilla, renegade, fugitive communities in the south of France, in a place called Cévennes. It’s very, very rocky and unforgiving, right? <laughs>, rocky terrain.

He led this community there. And non-verbal autistic children were part of that community. Mind you, he did not try to heal them, to reform them, to explain them. Instead, his work, along with his accomplices was to accompany them, right? Because he noticed that trying to reform them was to impose the supremacy of what we might today call neurotypicality.

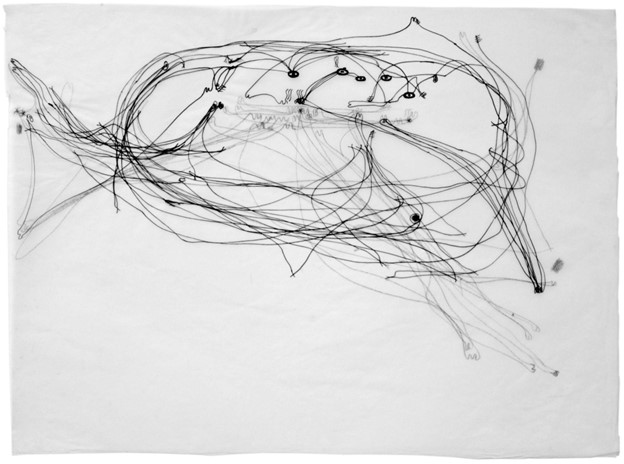

So he was like “I refuse to heal them. I’m gonna accompany them. You know what we’re gonna do? We’re gonna start cartographical projects. We’re gonna trace their wandering”. So he called it lignes d’erre, which is wander lines. And the accomplices would trace the so-called mad wanderings of these children as they just wandered in those large fields. Here’s what’s very interesting about this. You call them non-utilitarian wander lines, right? But there was something about them that was quite fascinating because they discovered that those children seemed to be tracing out unknowingly the underground circuits of water.

Think about that. Their so-called nonsense walking was tracing out the root and the passage of water underground. That’s the question I ask: what are we missing with our so-called normalcy? What are we missing with our so-called wholeness? You know, I do not dispute the ways or critique the ways people use wholeness. Semantics always comes in. You can use it in any way you want. I’m using it in a very strict sense of noticing that sometimes when we speak about wellness or health, we are reinforcing colonial boundaries of closure. We’re reinforcing the walls with which we have used to name our bodies.

And I like what I’ve learned here in India. I’m married to an Indian, my children are Indian, my friends are Indian. The land has taught me something. It says in a proverb that “name the color, blind the eye”. Let me say this, sister, I convey blessings on you, and I ask my ancestors to bless you, to bring fugitive communities that will support you and those of you in such circumstances. I’m in that circumstance as well. We don’t want to close you up. We don’t wanna be closed up.

We want the cracks to breathe because that’s how novelty—that’s how transformation happens: in that place where we say “no, I don’t want to heal. I’m gonna stay with this trouble and see where it takes us.”

And those wander lines do magic things. Yeah. I’ll just say that.”

What does it mean to stay with the trouble that is unknown? Where the open crack, the unsealable wound, the generative incapacitation brings in an unquestionable need to create spaciousness between call and response. Between dysfunction and the urge to normalize. Between the plea and the conditioned reaction. Between trauma and healing. Between the terrestrial map, and subterranean water streams.

I felt as if I had received a very important message. I knew that this is what my project would have to be about—refusal to heal back into the systems of degeneration. To expose and meet the part of me, and part of the collective psyche that manifests in various “ailments”, physical or mental conditions, that stop us in our hypnotic and inertive tracks. To celebrate and outline those parts of us that open cracks in a systemic, methodical rhythm of modernism–as inevitably, they open opportunities for transformation.

In part three of the article series I expand on the notion of refusal to heal, as well as share the mycelium sculpture project trajectory.

Here you can read the first part and the third part of the article.

Rūta Žemčugovaitė is a Berlin-based multi-disciplinary artist, researcher, & facilitator of transformation. She writes Regenerative Transmissions, a newsletter about a deep desire to move away from extractive relating to the living world, into regenerative and mutual interbeing. Her work inquires into regenerative futures through researching mycelium as a co-creator and designing experiences of perception change for more-than-human imagination.