In a three-part article, Rūta Žemčugovaitė reflects on Flourish! the Learning Journey designed by One Resilient Earth that she joined in September 2022. She also highlights the influence of the Learning Journey on her artistic practice. This third part of the article addresses What Happens When We Resist Healing Into the Old Systems? It introduces Rūta’s Mycelium Sculpture and Redefining Interspecies Relationships.

In article two of this three-part article series, I wrote about the importance of asking difficult and vulnerable questions. Asking these types of questions in the Flourish! learning journey has opened new pathways of meaning for me as an artist, especially for my latest project Refusal to Heal, which I will share in this article.

Refusal to Heal

I’ve spent most of my teenage years and twenties following the curved lines of healing. Hundreds of books, courses, protocols, diets, and healing modalities. Realizing and forgetting the revelations—entering a path of healing can lead you into an obsessive purification from all parts of yourself that seem to go against your desires, or sabotage your ideas about how life should look like. Sometimes, we feel as if our bodies and psyches refuse to heal, refuse to change.

But what if all the unwanted thoughts, emotions, feelings, and physical issues are not in the way of our desires? What if all these unexplainable “ailments” that we face are here to teach us about our truth and what it means to refuse to heal into internal and external systems of self-denial and oppression?

The underlying essence of healing on society’s terms means adapting to profoundly degenerative structures that allow further extractive relationality. Here, maladaptation is framed as healing that allows us to come back into colonial architectures that expect us to be agents of productivity, further fueling the paradigms of exponential growth.

The question arises: what is true healing?

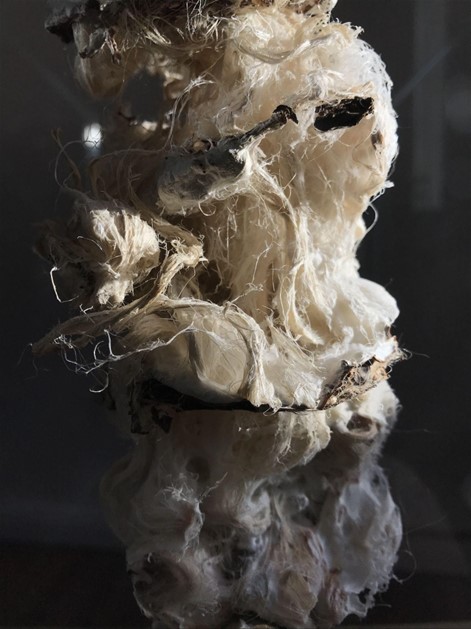

My current project Refusal to Heal explores the juxtaposition of healing. It is a fungal mycelium sculpture, shaped into a sculpture of a human body. Here, mycelium is a co-designer, co-artist, and co-remediator. It lends the quality of an alien, unknown, distant, yet deeply familiar. Allowing us to look at and reconnect with the alienated parts of the collective psyche and the collective body.

Refusal to Heal aims to reveal the parts of the human psyche that want nothing to do with healing back into society or a life that will not change. These parts of us manifest as inexplicable ailments, chronic conditions, somatic disability, neurodivergence, ADHD, high sensitivity (HSP)—everything that is perceived as unproductive—causing the slowing down of a growth-obsessed economy. Resigned to the shadow, these parts of us seek relationality, unconditional being, truth, and a conversation no one dares to have. These parts are described as resistance that will not cooperate with the loudest agenda. We can recognize that the rising mental and chronic health crises shine a light on our unconscious personal and collective resistance to participate in systems that are degenerative and opposite of life-affirming.

The project aims to provoke a public discussion of what it means to adapt to systems detrimental to our well-being, and what happens to our body-mind when we overlook signs of internal resistance. Leading traumatology researchers suggest that trauma happens when we lose connection to our authentic selves, replaced by adaptation to surrounding circumstances. In a viral article “I’m a psychologist – and I believe we’ve been told devastating lies about mental health” in The Guardian, author and clinical psychologist Dr. Sanah Ahsan writes: “But change won’t happen without us: our distress might even be a sign of health – a telling indicator of where we can collectively resist the structures that are hurting so many of us. <…> The most effective therapy would be transforming the oppressive aspects of society causing our pain. We all need to take whatever support is available to help us survive another day. Life is hard. But if we could transform the soil, access sunlight, nurture our interconnected roots and have room for our leaves to unfurl, wouldn’t life be a little more livable?”

Body as the Subconscious

By externalizing mycelium from subterranean worlds into a 3D shape, the project makes an analogy of bringing the parts of ourselves into the light of consciousness. Out of the subconscious (subterranean) to conscious and visible (above the ground). As below, so above.

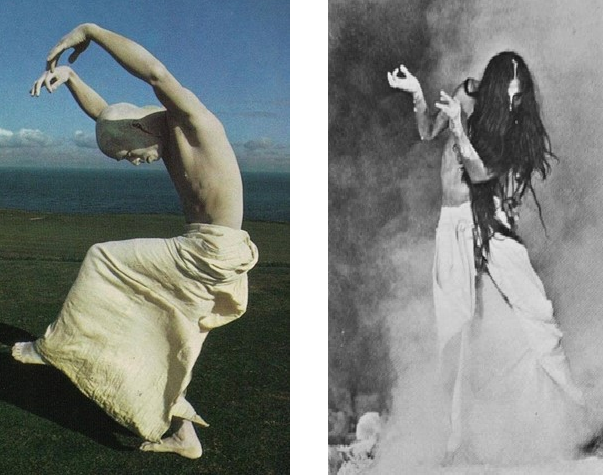

Alternative movement practices, such as contemporary Japanese dance Butoh (舞踏, Butō), invite us to perceive the body as an archeological site: “to dig up gestures or figures that have been buried in the darkness of history, and to float them onto the white-painted flesh”. Mycelium too, with its white fleshy texture, floats up the fugitive, the alienated. Yet, the body of mycelium always shapeshifts into the correspondence of another body—roots, underground critters and bacteria, soil, wood, and perishable materials, surrendering themselves into decomposition.

Mycelium, as an archeological ontology of memory, is never in one place. It shapeshifts with every change as the memory of the landscape transforms with every emergence, birth, and loss in that landscape.

Transforming Extractive Relationality

The second topic builds on the first one by examining our extractive relating to fungi. While mycelium and fungi are becoming popular, promising, and innovative design choices, one crucial question remains: Are we using the same extractive attitudes towards fungi, masked under the guise of “the greater good”? The rising green economy and innovation in the field of bio-fabrication have opened up opportunities to use biomaterials as means to an end to a more “sustainable” future. As we discover new ways to generate biomaterials, we risk overseeing the living organisms as means to an end—deploying the same extractive methodologies as we have done to other living systems and natural materials.

“The end justifies the means. But what if there never is an end? All we have is means.” Ursula K. Le Guin

When sharing that I work with mycelium and fungi, many people ask if they can use it somewhere—if mycelium has usability. This question overlooks the essential nature of fungi on Earth and reveals a myopic outlook on human and more-than-human relationships. With discomfort, in a growth-centric society, we can say “Yes, it can be useful: for another biotech venture, zero-plastic packaging, architectural composites, animal meat for leather replacements, or many other innovative solutions”.

A study reveals that the years 2009-2018 yielded 47 patents and patent applications claiming fungal biomass or fungal composite materials for new applications in the packaging, textile, leather, and automotive industries.

To be able to patent an ancient living organism seems problematic and opens up a debate about the ethics of relating towards more-than-human. A limited understanding of what “useful” is, makes us perceive other species only from an extractive lens. In fact, a recent study speculates that fungi evolved on Earth between 715 and 810 million years ago— highlighting that fungal mycelium has been more than “useful”, rather, indispensable and vital for life’s evolution on Earth, including in the development of root systems in plants.

The inquiry into “usefulness” allows the public to shift relating from extractive thought patterns such as “what can I get from fungi?”, and towards wonder, curiosity, and desire to explore fungal intelligence, networks, systems, relationships, and speculate possible sentience. The artwork invites us into humility and reverence toward fungi: how can we learn from fungi, while developing new kinships and relationships with these incredible species? Can we move beyond the means of sustainability and towards regeneration? Scientists such as Jane Goodall or Merlin Sheldrake tell stories of change while living alongside the subject of study: the more we learn about a subject, a species—the more that wholistic knowledge allows us to be transformed into new ways of relating: from extractive to kinship.

The artwork invites the public to reimage our relationship with fungi — not just from extractive “green growth” lens, but to reestablish an understanding of deep interdependency and care. Can we not only see fungi and mycelium as an emergent design biomaterial but as species integral to our existence? Can we examine practices of extraction before mass-industrializing fungal species for “green growth”?

Refusal to Heal is an ongoing project, currently in the testing and prototype phase.

Here you can read the first part and the second part of the article, leading to ‘Refusal to Heal’.

References

- Gabor Mate, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture (New York, Penguin, 2022), 289

- Cerimi K, Akkaya KC, Pohl C, Schmidt B, Neubauer P. Fungi as source for new bio-based materials: a patent review. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. (2019) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31673396/

- S. Bonneville el al., “Molecular identification of fungi microfossils in a Neoproterozoic shale rock,” Science Advances (2020). advances.sciencemag.org/content/6/4/eaax7599

- Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures (London: Penguin, 2020)

- Bessel van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in Healing of Trauma (New York: Penguin, 2014), 80

Rūta Žemčugovaitė is a Berlin-based multi-disciplinary artist, researcher, & facilitator of transformation. She writes Regenerative Transmissions, a newsletter about a deep desire to move away from extractive relating to the living world, into regenerative and mutual interbeing. Her work inquires into regenerative futures through researching mycelium as a co-creator and designing experiences of perception change for more-than-human imagination.