Barnaby Steel, artist, director and creative director of experiential studio Marshmallow Laser Feast, and Laureline Simon, founder of One Resilient Earth explore how virtual reality installations can fuse science and art to make us fall in love with nature, and transform how we interact with the world.

Laureline: Because of lockdown, I have not had the chance to experience Marshmallow Laser Feast’s immersive art installations yet, but I am fascinated by some of the images and videos I have seen. I am thinking about ‘We Live in an Ocean of Air’, which follows the journey of our own breath from body, to plant, to planet. Just the title of the virtual reality experience has made me feel the world differently, while some of the videos on your website give me goosebumps. You have also created other installations such as ‘Treehugger’ or ‘In The Eyes Of The Animal’. It made me curious. How do the visions for the installations emerge? How does the team get started on each new project?

Barnaby: Our adventures in virtual reality and non-human perception started about 5 years ago when we were approached by the wonderful ‘Abandon Normal Devices’ festival in partnership with the Forestry Commission to create an artwork for the sculpture park in Grizedale Forest. At that time a number of influences collided to shape our future trajectory. One such influence was Satish Kumar’s Soil Soul Society: A new Trinity for our Time. Satish Kumar puts forward the realization that personal transformation comes from the heart and not the mind. He questions how anyone could shift from a consumerist mindset to a conservation mindset without falling in love with nature and recognizing oneself in nature. In other words, having a deep transformative experience is necessary for our hearts to open up and feel that connection. Conversely, without that falling in love, taking care of the Earth is always going to be a challenge. With so many people being born in cities the opportunities to have deep experiences of nature can be limited but also some of the ecosystems we are destroying are remote, hostile to visit and in certain cases tourism can cause its own negative impact. Anyway, all this got me thinking about the possibility of using virtual reality to bring the wonders of nature to the home, the gallery, the classroom.

Barnaby: Another major influence is scientist Richard Feynman, he exudes the pleasure of finding things out and puts forward the idea that a scientific understanding only adds a sense of awe and wonder of reality, it never subtracts. He’s got a wonderful interview on YouTube where he talks about how an artist might have a heightened aesthetic appreciation of a flower, a sensitivity to its texture and details in a way that a scientist might not have. But when a scientist looks at a flower, he can see the beauty of the inner workings, for example they might understand that the reason the flower is red is that it reflects that particular wavelength of light, and that the color has co-evolved in relationship to the eye of a pollinator. It asks the question ‘does a pollinator have an aesthetic sense in the same way humans have ?’ There are the inner workings, the photosynthesis, the plants ability to eat sunlight… All these questions only ever add to a sense of awe and wonder of a flower. It’s this relationship of scientific understand to awe and wonder that we feel when we create our work and we hope that translates to our audience.

And so, in a happy accident in time, these things came together in our minds, and we used technology to create a deep experience of nature, building on how science reveals a world beyond our perceptions in ways we could never invent. Those stories are full of poetry and beauty. Our projects emerge out of this connection of science, deep experiences of nature, and the last part is just about being able to engage with new audiences by the fact that we are using new technology.

Laureline: As you mentioned, the virtual reality experiences you develop are heavily informed by science or represent some scientific facts and findings that may not be visible in our realm of perception. As artists, how do you acquire this scientific knowledge? How much work does that entail for each installation?

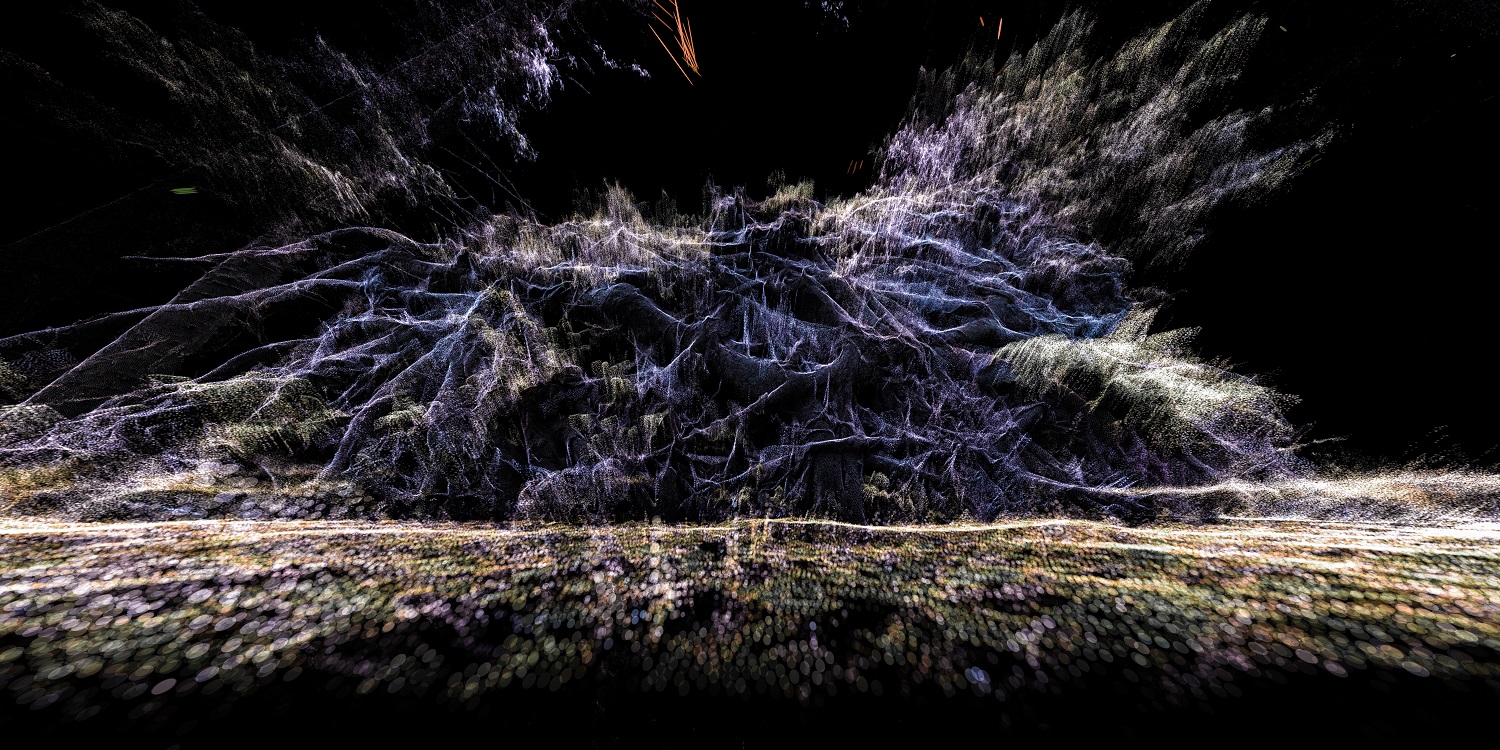

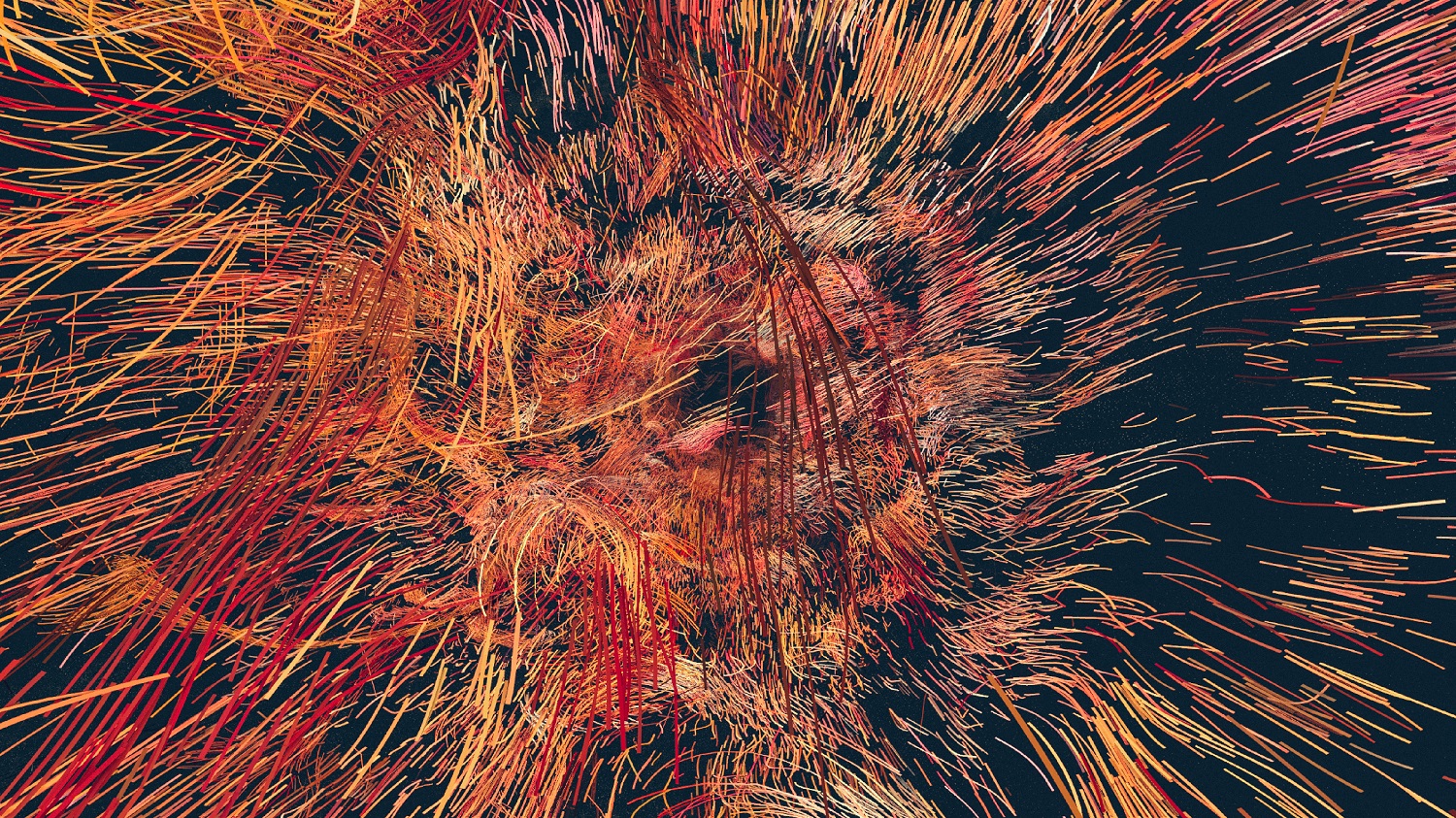

Barnaby: We all share a passion for science within the studio. I think that curiosity comes from the great mystery of who we are and how we got here. I see science as the forefront of our inquiry into the nature of nature, driven by intuitions and measured with instruments that extend our perception way beyond the limits of our senses. We apply that scientific inquiry to our work and for example when we were making ‘In the eyes of the animals’, it was like doing a mini PhD. To summarise the project, it was a journey through a forest ecosystem seen through the eyes of a midge, a dragonfly, a frog and an owl. Each organism has a different flavour of perception, a unique perspective on the shared forest environment.

One fascinating consideration is how time can compress and expand depending on what organism you embody. Humans can watch a film at 25 frames a second without perceiving a pause – the images seamlessly flow. A dragonfly is a finely tuned killing machine with eyes so close to its brain that its effectively living life at 300 frames per second. When it watches the same film it sees a slide show, each frame holding for an equivalent of 12 seconds. A dragonfly has better colour vision than anything in the animal world. It can see well into the ultra violet and infa red spectrum through its almost 360 degree eyeballs. We can get a glimpse of those colour spectrums through specialised cameras and this informed the way we created that world. The owl on the other hand has eyeballs cemented to its skull, to look around it has to move its head, hence its amazing ability to rotate its head in almost any direction. Its eyeballs are the equivalent of a 200mm zoom lens, giving it the ability to read a newspaper (if it so wished) from the far end of a football pitch. The more you discover the more precious these critters become and we all noticed a shift in the way we experience a forest after making this project.

Laureline: Do you also collaborate with scientists for some projects?

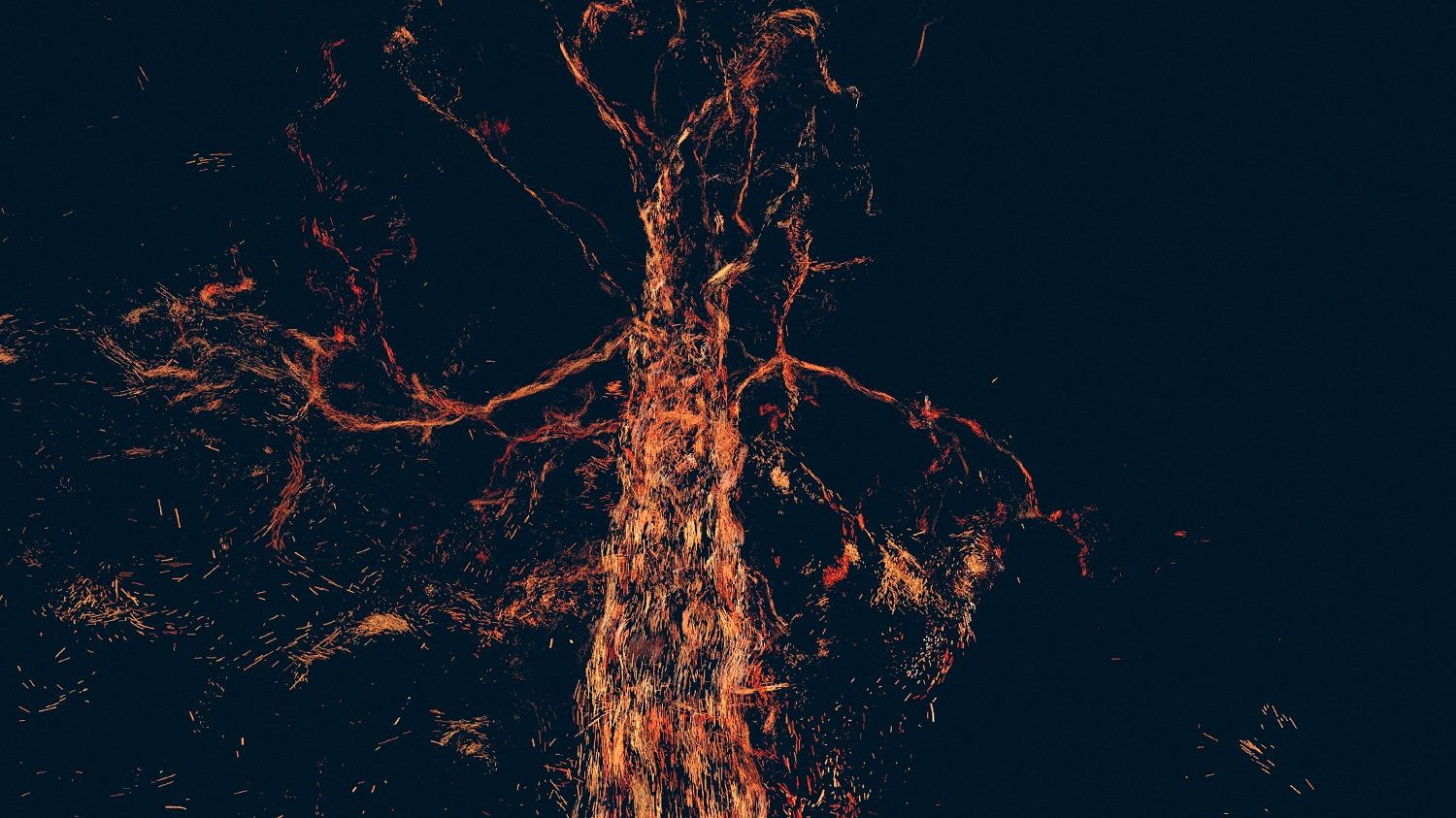

Barnaby: We collaborate with many amazing scientists, one of which is Merlin Sheldrake. He is an expert in all things fungi and we have some future projects planned with him where we peer beneath the soil, deep into the wood wide web. It’s a treat listening to him talk about his explorations, and it provides us so much fuel to create virtual experiences. He very neatly explains that we are not individuals, no living thing is, every organism is a symbiosis. Seeing your own body as an ecosystem or a forest as a super organism is a wonderful lens on the vast tissue of existence of which we are a part. Recently Merlin planted this knowledge down for all to read in his new book: Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures.

There is a humbling quality to science stories that often highlights the limits of human perception. Although our perception is beautiful and rich and our bodies are amazing, it is just one lens on reality, one narrow little channel. Science can broaden this channel, extend our ability to see, to hear, to sense the world in new ways. As an example through incredible instruments like Hubble space telescopes we can peer back to the birth of the universe, through a LIGO we can read ripples in the fabric of spacetime using the wavelength of light as a measuring stick, through MRI scans we can see inside the body and electron microscopes reveal structures way beyond the limits of our eyeballs. All this technology is showing a reality that we can’t sense and part of our fascinating journey at Marshmallow Laser Feast is that we can now design virtual reality experiences that make that world tangible, deepening our connection to reality.

When considering seeing the world through the eyes of another animal we refer to Thomas Nagel’s ‘what is it like to be a bat?’, he highlights the issue that you can’t translate a sense that you don’t have to one that you do have. As an example if I’m a blind person and somebody is trying to explain to me what a specific object looks like, no words could ever articulate the richness of the seeing that object. The texture, smell, weight and sound of an object can give a blind person a clear sense and from that they can maybe imagine what it might look like. I think that the same goes for exploring the elements of the more than human world: there is always an element of poetry in the translation from a sense we don’t have to one that we do have. Why is this interesting? Well Michael Pollan hit the nail on the head, “Looking at the world from other species’ points of view is a cure for the disease of human self-importance.”

Laureline: As you’re talking about this powerful shift in perception, I am curious to know how people react to your installations? Are there any variations in the way different generations respond to the artworks for instance?

Barnaby: Children have less inhibitions when they put the headset on. With one of our installations ‘We Live in an Ocean of Air’, children just wanted to run around in the rivers of oxygen, playfully exploring their breath, while sometimes adults can be a bit stiff – that said we had some 90 year olds pass through the installation so stiffness can be expected. ‘Ocean of Air’ was designed with embodiment of an avatar in mind. We used a breath sensor and a heart rate monitor in combination with a full body tracking virtual reality to allow participants to re-discover their body within the virtual world. The concept was to make visible the rivers of oxygen and carbon dioxide that connect plant to animal, to explore those flows as they ripple into your branching lungs, flood your heart and from that centre, branch out to feed every cell in your body. In the same breath, umbilical like rivers of carbon dioxide leave your lips on route to stomata in the plants, flowing photon fueled photosynthesis, the process at the route of all life. We’re also conscious that when people come out of the experience, it’s really important to give them space just to digest and ground back into their bodies. Both really old people and young people have reported a sense of ‘otherworldliness’ that they have never experienced before.

Laureline: Reflecting on this ideas of ‘otherworldliness’ did you get the opportunity to test the virtual reality installations with indigenous people who have a strong connection to the forest, including indigenous knowledge holders who may have access to wider perceptions of reality?

Barnaby: A friend of ours, and great producer, Ginny Galloway, was in touch with the Yawanawa tribe, which is Amazon-based and who had tribe members passing through London. I was actually away at the time but the group came to the studio with her, and they tried ‘Treehugger’. One of the elders said that he saw that there is another doorway to plant intelligence, which for them is experienced though ayahuasca. So it was great to have such a compliment. But it’s a sensitive point. I guess that the level of spiritual transformation that is going on within ayahuasca is so profound that any kind of virtual reality experience would just be a very diluted echo of that. On the other hand our work isn’t looking to mimic any psychedelic experience, we are looking at the forest through a scientific lens, revealing the underlying rhythms that underpin life – like the flow of water, air and nutrients. It no surprise that an indigenous perspective would share much in common with the scientific lens, in a way both are observations that build a heightened sensitivity and awareness to a forest as a living breathing super organism. But I’d be cautious about comparing virtual reality experiences to any kind of shamanic rituals.

Laureline: Without comparing, I was wondering if you had noticed any changes in your connection to your own body, to your community and to your ecosystem after working on so many artistic projects that focus on showing our interconnectedness with the natural world?

Barnaby: It’s all unfolding. It’s a process of change, a movement towards a deeper appreciation of the everyday deliciousness of existence. Through that comes a deeper engagement with the world we will leave behind when our light fades out. What is the ripple that we create through our lives and how is it affecting the future generations of people, trees, snakes, sloths, snails…? It’s funny. Life has a way of guiding you through synchronicities. When you are on a certain path, so many unlikely souls pass your way, almost like guardian angels. I met a guy on a plane flying to Lima. I was looking at a giant sequoia tree on my computer when he leans over and says: “Oh, the reason those trees live so old is because they breathe so slowly.” And I was like “Who is this guy? I like the pine of his cone! “He happens to be a tai chi master. I am still in touch with him and he gave me many beautiful steers.

One such steer is a question that if everybody could answer ‘yes’ to it, the world would be a much better place: “Do your actions have a positive impact on people and the planet?” by saying yes, we would have solved a lot of problems. It’s a kind of accountability and it requires a thoughtful process. For when you dig into it, it’s very hard to answer yes, but having that question floating in your head can act like a compass. We believe we are working towards a future where immersive experiences could nudge a Tech savvy generation towards conservation and we are at the start of that journey.

Laureline: And have there been any ideas, realizations or epiphanies that transformed the way you relate to the world during that process of trying to do good for people and the planet?

Barnaby: Sometimes you wrestle an idea into being and that seems to come more from the intellect. At other times true inspiration hits a deeper level of idea or realisation that feels like a wave passing through you, the process of riding that wave is one of surrender not struggle. It can also be seen as a river that feeds you, the vision carried by the stream wants to manifest into reality and it’s got nothing to do with ego or ownership and it has everything to do with surrender, widening your funnel and being sponge-like so you can absorb before crafting the work. So it’s been a transition from being a more egocentric director to being at the service of something beyond me. And with that shift comes the question of intention, “what is the real intention?”. That’s a deep one to bow to because there are ideas like “oh, it would be great to be a famous artist, to receive recognition for my work” But actually, the deeper intention of the work has to challenge those ideas and we have to ask the question of what the real value is.

David Attenborough’s nature documentaries come to mind when I think of a person dedicated not to fame but in service of nature. His films have touched so many hearts and minds, and if I can have anything close to his legacy it would be a treat! I think virtual reality can take us one step closer to nature than filmed documentaries. Rather than having an experience of nature through the rectangle of a screen, being able to embody other organisms is a whole other level of connection and empathy. It also takes us out of our own body which breaks the human centric feeling that reality is just what we see.

It’s early days but I think there is a power in the awareness raised by embodying other organisms. This leads back to this inner feeling that I’ve got of there being an underlying awareness that flowers through us, as well as through a blade of grass – this underlying life force that’s animating me and everything else flowers from the same one source. In some ways virtual reality can give us this disembodied awareness and maybe awaken that connection. That’s a feeling though, just an intuition, which is not measurable and could be heavily influenced by my Alan Watts fetish.

Laureline: The connection between science and spirituality is particularly interesting to us at One Resilient Earth, as ancient wisdom can sometimes open up perspectives which are confirmed by the latest science or which we would like to further investigate with the help of scientists. Could you share more about how science and spirituality interact in your work?

Barnaby: It seems to me that science and spirituality are pointing in the same direction. I am reading a book on gravity by Carlo Rovelli and he talks about how the fundamental nature of reality does not require time. Actually, time as we perceive it emerges through the nature of our memory. If you woke up in the morning and you could not remember anything, you’d have no way of describing up from down, a tree from a dog or your hand from a rock. Everything would just be. In a state of pure un-labelled existence. This shares common ground with the shedding of ego in spiritual practice, connecting to a deeper consciousness unlabeled and interpreted by the mind. Those who have managed to shed the smoke screen of ego describe that underlying reality as an experience of pure love, not an empty void of nothingness but a womb full of the creative potential of all things. I’ve had experiences in my life that gave me that feeling.

Touching again on perception, it’s interesting to consider the real impact of memory on who we are and how we interpret the world. In a way we are story machines, every moment, every experience builds a data base that the present moment is filtered through . This makes me think about the power of stories and experiences to mould perception and shape minds. Maybe my calling is to sow scientific stories of awe and wonder that re-connect us to the bonkers reality we find ourselves in. Richard Powers in The Overstory (one of my favourite books of all time) says something like ‘us and trees, gliding through the milky way together.’ I love this simple image but to go a step further, trees have been gliding through the milky way for a lot longer than us, we rely on trees for life but they don’t rely on us for life. We are passengers on their good ship earth and we are deeply connected.

Barnaby: Carlo Rovelli also talks about how there are no static objects, just interconnected processes unfolding. He gives the example of a kiss as a happening, a moment in time, and a rock as a static thing, something you can observe over years without seeing any change. But a rock is like a kiss as well, just on a different timescale: it’s a coming together of elements before they fall apart and become something else. So when we start thinking about everything not as objects but as processes it starts to appear that we are indeed ‘the big bang still banging’ as Alan Watts puts it. Put another way we do not arrive on this earth, we arise from it. The illusion of separation and the feeling that we are separate individuals runs deep. The nature of the way our eyes work positions us in a unique point in space, only that, and maybe the skin gives a feeling of separation. A new project I’m working on at the moment ‘The tides within us’ explores the human body as a flowing event, more like a whirlpool than anything static. Peering beneath the skin we reveal a branching being, rivers of oxygen feeding billions of cells. To use MRI to peer into the body is a reminder that many moons ago the animal kingdom branched off from the plant kingdom and we clearly share many similar structures and DNA. I read somewhere that we are all skin encapsulated ecosystems, neatly packaged to move!

Laureline: It feels like it would be a great realization to have early on in life. People from our generation, at least in our circles, are coming to this type of realizations through different routes today. But would it not be great that children have these realizations regarding interconnectedness, time and the convergence of science and spirituality as they grow up? What would their lives be like? So, I was wondering if you are involved in any discussions to make those virtual reality experiences part of educational curricula. Are you exploring this idea at the moment?

Barnaby: When we sit at our board meetings and dream the future, there is a big fat arrow which is basically how to reach millions and millions of eyeballs. Our metric is how many people can actually experience our work and, at the moment, it is not very many people. But we’re beginning a much longer journey and our vision is to focus on getting funding to create the work at larger scales and very specifically to release our virtual worlds to the home and education spaces.

Barnaby: Through the project I mentioned earlier ‘The Tides Within Us’ we’re working with the Fraunhofer Institute MEVIS lab on the scientific data and we’ll be doing a whole education package – we’re super excited! They’re using very high-end MRI scanning techniques to see inside the human body. They released an amazing video of blood flow through a heart which looks like birds in murmuration and really inspired the project. Together we are exploring the flow of oxygen through the cardiovascular system of a giant virtual human. I can image when the project is finished schools will be able to go on hikes through the human body much like they would hike through a forest. Maybe we can get some of the world’s leading scientists to narrate those journeys through the human ecosystem.

The project also raises fascinating questions in terms of education: What impact does the embodiment of research findings have in terms of how you remember something? Does that create a curiosity to learn more?

Laureline: And regarding the impact of the artistic experience over time for each viewer, have you thought of ways to keep this feeling of interconnectedness going once the experience is over? Are there some practices that would complement the experience and make the feeling of symbiosis either last longer or expand over time?

Barnaby: Each project we create starts with a real ecosystem that we 3D scan and translate into a virtual representation. These virtual worlds are not one-off events with the idea of next, next, next. They are places flowing with a million organisms and potential interweaving narratives and we plan to keep adding new threads over time. With this in mind we hope that they can become a place where indigenous wisdom and spiritual practice blend with science and art.

Imagine doing a breathing meditation whilst gliding through a CT-Scanned leaf that feels like a vast vaulted cathedral, each out breath feeding the photon fueled splitting of water molecules, each inbreathe sucking the waste produce of photosynthesis into your branching body… There’s also a lot of scientific data on the brainwaves that you get in the state of oneness or flow. It’s interesting to think scientifically how to create feedback loops that might allow you to get to that state more easily. That’s one moment we have been thinking about. The connection to a real place is important, as my good friend Louie Schwartzburg says, ‘we protect what we love’ and maybe as our projects grow we can nudge people towards deeper connection and conservation of the ecosystems we are part of.

Wow ! Fantastic !!