Nicholas Galanin – Yéil Ya-Tseen, Tlingit/Unangax̂ multi-disciplinary artist, and Laureline Simon, founder of One Resilient Earth, explore the use of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, the return of Indigenous objects and land to their community, and opening spaces to create something new.

Laureline: I am very grateful you are taking the time for this dialogue. I came across your powerful and eye-opening work, Created to Hold Power (Intellectual Property) via the Anchorage Museum, as I was diving deeper and deeper into the role of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge in addressing climate change and environmental degradation. In a recent dialogue on Tero Magazine, we questioned why Indigenous knowledge holders are not given center stage in leading the transmission or preservation of their knowledge. As an example, when the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples platform was set up under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to foster the sharing of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge in relation to climate change, countries negotiated on giving seats at the table to Indigenous people. They do have half of the seats now, which can be seen as good or as not enough, but this was not a given in the original mandate in 2015.

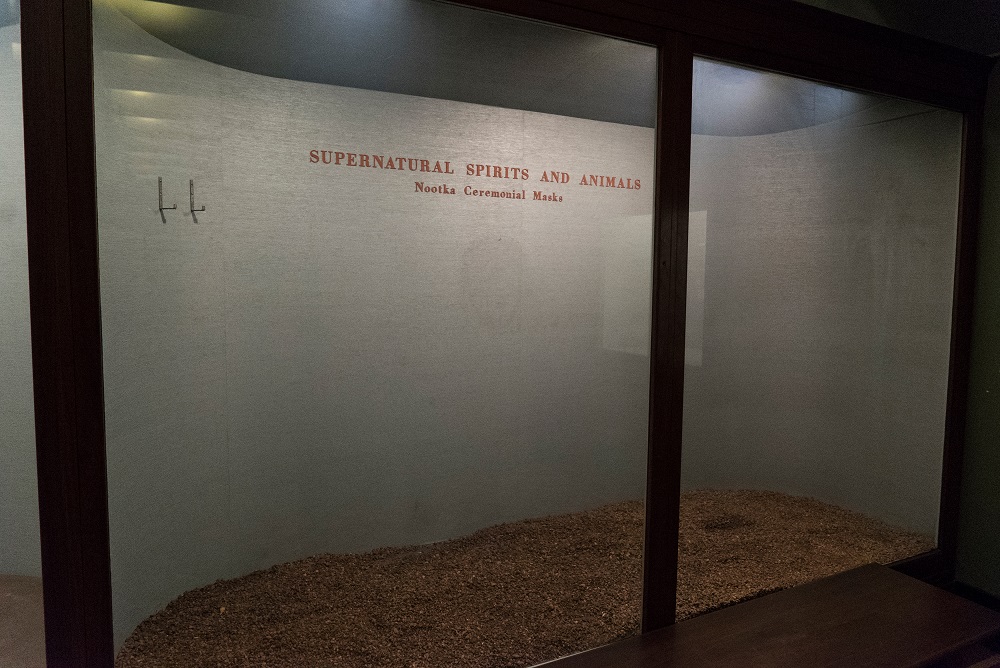

Besides, the more I understand about free, prior and informed consent for the use of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge, the more I realize that modern western institutions are unlikely to provide for the cultural and spiritual dimensions of that knowledge, which is clear in Fair Warning. I also had to face the theft of Indigenous objects that populate our European museums, and how the presence of those objects feels wrong at a deep level today. As we ask for Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and support in dealing with the ecological crisis, such a theft cannot be silenced. More importantly, I fully agree that returning those objects would be beneficial for the “health of those objects, for the health of the communities that created them, and for the health of the communities that took them,” as expressed in Architecture of Return. The escape route that you have created feels like those Indigenous objects are already being freed at an imaginary level or in a possible future, which is quite liberating. Can you tell us more about this work and its context?

Nicholas: As an Indigenous person, our historical inheritance, objects, even ancestral bones are often held in museums. So, this work, Escape, was showing a way out of these prisons, which is what museums are essentially. And the way out is returning the objects. There are repatriation conversations happening today, that are oftentimes heavily bureaucratic. I have also heard conversations where the claim is that without these museums, cultures would be lost. But, the irony is that those same communities that built those museums are often the ones that have pushed out these cultures and communities in that process. So, the art piece is an escape route or it’s a plan of removal or it’s a possible future as you mentioned. A vision. And as a vision, it doesn’t just stop at the objects. It continues and goes to other larger conversations like land. Oftentimes these oppressive institutions are aspects of our societies or communities that are trying to maximize their return on our objects, on our land, on our bodies. It’s very common in white supremacist narratives of culture where things are not quickly changed or shifting because returns are still being maximized.

Laureline: I agree on the irony of having powers that have so damaged peoples and their cultures historically, subsequently promoting the conservation of some knowledge, objects or cultural expressions they find valuable, while defining the rules and purpose of that conservation process. If we had thriving Indigenous communities, with full access to their land and all of their rights respected, who would worry about the conservation of the vibrant, living, continuously growing knowledge systems and practices of Indigenous peoples? Only if we assume that Indigenous peoples or their culture are in the process of disappearing, do we feel the need to keep their intellectual productions and cultural expressions, or pieces of them, for them, in boxes, including in virtual spaces managed by international organizations. Maybe we should expose and question our assumptions more.

Nicholas: Those institutions and spaces also uphold the narrative that white supremacy is an authority on Indigeneity, and that is highly problematic and really oppressive to our communities and our knowledge. Where our communities have not only had their objects physically mined, but even our knowledge is mined at certain points when it’s profitable. And then, you know, of course, it’s also heavily homogenized through academia, or anthropology, and then it’s presented, as truth or knowledge after it goes through that process.

Laureline: True. And I often wonder how to best explain to non-Indigenous people that Indigenous peoples’ knowledge is fundamentally different from western knowledge as I am beginning to understand it myself. That the knowledge comes from the land, that it has to be alive, or that it holds power. It seems that a better understanding of that difference could help limit attempts at homogenization of Indigenous peoples knowledge and at cultural appropriation. Do you have any thoughts on that point?

Nicholas: I don’t have a simple answer to that, except obviously, that giving us equal rights, human rights, etc., is a good starting point. And then, obviously a big part of colonization in that process of genocide towards our communities was to displace and remove and break down. And that still goes on today, in a lot of ways, for instance, in our access to land. I have to check the exact statistics, but I think less than 3% of land in North America or the US is owned by Indigenous people. That’s a major settler occupation on unceded Indigenous lands. With that comes a lot of other powers that are built into the land and upheld, that build wealth for nations. So, these are all starting points. Land back is the movement that a lot of people talk about. And cultural sovereignty. A lot of the tools that were provided by the government are generally tools that aren’t in our favor, ever.

Laureline: Can you tell us more about the vision of a future where Indigenous land would be returned, and all rights would be fully respected? What would it look like?

Nicholas: We fight for it every day, all the time. And in our little ways, in all ways, in our resilience, so that our communities and cultures continue to live. The other ways that we access it are through learning and teaching, education, understanding and sharing our connection to this place, which is vital to the health of the ecosystems of the world. You look at things like the fires that have been happening in California or even in Australia. The Aboriginal community in Australia did controlled fires for a very long time. After that was banned by the government, forest fires clearly became a bigger problem.

Laureline: And do you have a vision of what could be the new use or uses of museums once all the Indigenous objects are returned and we have those empty spaces available?

Nicholas: It’s not like we’re ever going to stop sharing and creating culture and works. There are new things happening continually, and all these things can be shared in ways that are not based on theft, genocide, and violence. That’s the way that these spaces can be reimagined and programed. The irony is that we’re filling museums’ walls and vaults with our historical objects and bones, yet we’re also not necessarily given access to those spaces with our living artists. They are disproportionately not represented in these modern art museums or spaces. So, there are very clear things happening here in where we’re allowed access and how, and where we’re not allowed access and how.

Nicholas: Of course, some of these things are shifting. If we look at history and recent history, it does seem slow, but it is changing. There’s more and more engagement in these institutions with the communities whose objects are in those spaces. There’s more programing surrounding that. And more open dialogue on repatriation is obviously happening. These things are happening, things are shifting, but it’s slow and it’s going to keep shifting. It’s not happening fast enough, but, people are resilient and continually in the fight for these things. There are also more and more of our artists that are in venues, collections, and celebrated museums like the MoMA, but it’s still very few. The power structures that maintain that are slow to shift.

Action is the most important thing really. It’s like land acknowledgment versus land back. Those are two very different things. So, it’s about what are people holding on to and why? And at whose expenses and costs?

Laureline: And do you think it will be important to keep places in museums that would be more about memory, telling the story of theft and genocide? Or should we focus those emptied spaces on new creations only?

Nicholas: I mean, they both serve importance roles and this can be done in ways where it’s healing and not, you know, continually traumatizing to the community.

Laureline: When we look at society more broadly, what is the best way for non-Indigenous people to support Indigenous peoples, including in relation to returning what has been taken, giving more space to thrive, and repairing the harm done? At One Resilient Earth, we thought about sharing your words and artworks, which have moved us profoundly, but can we do more or better?

Nicholas: I mean, I think that is part of the work. It is spreading the message, the agency and voice, and platform and space. Those are already modes of sharing and telling stories, or histories, or experiences. Everything helps. After all, we don’t really know how we will get in those spaces eventually. And, that’s what the power of the [art]work is supposed to be. It is supposed to be something that others can experience or feel or understand when they don’t really feel and see that in the day. Certainly, a lot of my work opens that dialogue to other communities and perspectives, so it can continue to do work so that I don’t have to be there every day saying these things all the time. The work is doing it. The work could do this forever as long as it’s around – using that platform in space.

Because a big part of our struggle seems to be aligned with intentional amnesia or, a community or society choosing not to acknowledge or see even the tribal communities as existing. There’s so many federally unrecognized Indigenous tribes in the US.

Laureline: I also have another question, which is if a non-Indigenous person is genuinely interested in getting to know more about a specific Indigenous culture, what would be the best way to learn? Is it even possible? Do you have advice on how we could do that in a way that does not reproduce old patterns of extraction, homogenization and profit-making?

Nicholas: I mean, it’s different. It depends on what you are seeking to learn. But essentially you really need to connect with communities. It’s probably the most direct way. Listening. This is probably a good place to start. There’re so many different communities, so many different needs. It’s very vast.

Laureline: And if we’re not in North America, or living close to an Indigenous community, but in Europe for instance, is there something specific we can do to support?

Nicholas: Sure. Send us the objects back!

Laureline: I definitely support the return of objects stolen from their community, and am in contact with a few networks and organizations. We would really like to help, and hope it can re-build some trust and improve relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Yet, it sometimes feel there is so much to do. Based on your experience and the resilience of your community, how do you keep going when pursuing this vision of a future that’s so different from what we are experiencing today?

Nicholas: You don’t have to take it all in one go. For me, it’s realizing that we come from a powerful community and history of people and places of power. That connection is what’s important: connection to the land. Maybe I don’t step back and look at things all the time, which is good, because otherwise it would be overwhelming. But it’s good to have a community. I feel like I have this luck.

Laureline: To conclude, do you want to tell us about some new projects that you’re working on?

Nicholas: There’s definitely some new projects coming up that I can’t mention because they’re not public yet. But you’ll see them within the next three or four months, which is really exciting. Some big projects that have been in the works for years. I just got the master’s from the studio back and I’m really excited.

Nicholas Galanin’s work engages contemporary culture from his perspective rooted in connection to land. He exposes intentionally obscured collective memory and barriers to the acquisition of knowledge, and critiques commodification of culture, while contributing to the continuum of Tlingit art. Galanin employs materials and processes that expand dialogue on Indigenous artistic production, and how culture can be carried. He lives and works with his family in Sitka, Alaska.

The indigenous peoples of the world, especially the Native Americans, have been and are suppressed because the governments of their respective countries are simply Embarrassed about their previous, illegal, ignoble, dishonesty and dishonourable treatment of the peoples. Again, especially White America: Their disgraceful attitudes. Embarrassment is a powerful emotion. It should not be underestimated.

Furthermore, these governments are truly afraid of the notion of Reparations. Let’s face it: The White Man has yet to embrace the fact that nobody can eat money.