Dom-an Florence Macagne spoke with One Resilient Earth, as part of the Re-storying Landscapes in a Changing Climate project. Dom-an reflected on how she has nurtured resilience and regeneration through combining the healing power of music, and the healing power of community organised organic farming in the Philippines.

Laureline: I am thrilled to be here with you today Dom-an. We are curious to hear first about your story, and how it ties into what drove you to develop your artistic nose flute practice, which is linked to your Indigenous culture.

Dom-an: Okay, you will not cry?

Laureline: I may cry but that is totally fine to me.

Dom-an: The bamboo nose flute is a long story.

I first watched my brother play it, and he was in such a serene state when he played by the window in the place where we grew up together as children. Then, we did not have concepts about poverty, in the economic sense of poverty now. We did not have electricity, or water flowing from the tap. Unfortunately, my brother was the recipient of violence from my mum, who seemed to lack control whenever she got angry. Despite that violence and simplicity in life; when I saw him playing the flute, he was in a state of bliss where nothing affected him. It was just the breath, and the beautiful music that I was watching. That was when I was around ten.

When I was sixteen, after a huge earthquake, I started hanging out with artists in the city. I was going to college, and getting interested in the flute. They were rare to find, only the performing artists had them, but I managed to get one. I felt, “I’m so shy, I’m so far away from what they are doing”. I started playing the flute, and joined as a volunteer in a Clergy Laity Formation programme. That programme was also advocating for the environment. They had a course called grassroots formation, and the challenge then in 1990 was global warming. I was naive, innocently playing the flute, and this guy fell in love thinking that I was serenading him with it. We became partners, got married, had children, and became comrades in work. The flute was not my companion then as I had my husband, my children, and all the work that I had to do. My brother went to prison, so I passed the flute on to him, because it was a relief for him. It might not bring him out of those bars, but it would keep him in that space of freedom, where nothing matters but the breath and beautiful music going round the place. It goes to the people around him, and it goes back to him. That was the beauty I knew.

We were activists. We were working on saving rivers from pollution and stopping open-pit mines. I was also beginning to advocate for organic farming as an alternative for young people, for hope. I was working as a community development worker in the mining community of the open-pit mines, and they were asserting their rights for the land. The environment was so destroyed, they were losing hope of what would happen to them. Most of them became out-of-school youth, as defending their small territory was primary over going to school. They had no livelihood because the big mines were trying to get the small mines that they were working on. Aside from agitating, mobilizing and bringing people to the city to resist and protest, I thought: there has to be some alternative. I explored and learned about organic farming through books. My mother was a gardener, but I had not learned how to grow plants. They were gardeners and knew more than I did, but they were using conventional farming, and not earning. I was challenged as a community organizer to know technical skills about organic planting, and motivate others to do it; and we started a small garden.

Then two of my brothers died in senseless violence, and in 2005 my husband was assassinated with twenty-two gunshot wounds. My temper was easily triggered while I was grieving, so I had to pull back from that community and let them do the gardening. It was an unfinished project. But, for them to start imagining that there was another way of restoring life in the fields, earning a living not from mining, and to get them away from alcohol, the mission was accomplished. I was twenty-eight then, I was burned out, and I even quit community-based organizing, it was so much for me to grieve and heal.

After my husband was killed, I raised a lot of questions. It was a dangerous path if the military kills your husband, so when you start asking people you do not expect evidence. Our activist colleagues used a materialist framework, and were objective and huge-hearted. But, I had endless questions about what really happened and why, and my questions were not being answered. I realized the healing process that I am wanting will not be answered with the same tools and the same people.

I asked for a bamboo nose flute, I was very grateful as most of the flutes were broken. That was when, within a month of my husband’s death, I and my young daughters felt the spirit of him, it felt so light. The television that he bought was switching on and off; the broken cassette player that I bought him suddenly worked. I realized, it was the spirit working, and that was it, I stopped pushing for answers. I played the flute instead to comfort my kids, I was able to write melodies and short songs. Like my brother, I got into this space to protect myself from the very harsh reality. Although I knew the reality, we also needed to sleep.

We need to lift ourselves up, never to lose hope

otherwise I would have died of loneliness. It is the same thing with those young people whose lands were being destroyed. Playing the flute and that kind of music reminds me that I still have sacred breath within me. I wish the assassin remembered that a person’s life and breath is sacred. The campaign for justice, for truth and to stop all these killings has to go on. The reason I was searching for answers was my search for justice. It would not be a stone thrown back at me that, “your husband was actually a devil, that’s why he was killed”. I had to make sure that I would not reach the level where I would suddenly doubt myself. That is really the beauty of playing the flute.

There is the obligation of advocating the value of life. These are activists protecting the very future that we want, protecting the very environment where we live, beyond their ideological or political leanings. This is what is in their heart. This is what we want to see. The new heaven and new earth: the beautiful land and living earth, the living planet.

I tell my story with the flute to create space and say thank you for listening to the music of the sacred breath. It connects them, makes them one with me, and I start to share my story briefly. I play the flute as an advocacy for upholding human rights, for asserting sacred breath, reminding each and everyone to value the breath, the breath of anyone beside them. In reality, there is no enemy. It is really wrong to shoot people. There is a larger challenge of the deluge, the floods or hunger. So, why do we kill each other? It is a way of communicating to the spirit of the assassin to say, even if they get paid in temporary money, it will not be sustainable or give them happiness. In the end, we might have held different opinions but we are all pursuing happiness. We are trying to struggle for a better future for our children.

It is going into deep reflections of the reality that we want to work for. A better, brighter future for the next generation. And, we want to do it alive.

I understand the fears and the losses of our former colleagues, but I had to focus my breath on the safety of my children. At one time, we had to leave the big city for safer space, just with our clothes on our back, because I was threatened. I was stigmatized for more than ten years. It is not easy to be labelled crazy while dealing with safety issues, while being a mother; but, I can’t wallow forever.

I was transforming, evolving and trying to reach out to larger communities. I started hanging out with other peace advocates and meditation circles. That is how I met Sarah [Queblatin, who leads the Living Story Landscapes Project]. Then, after two years, I came back to Sagada. Before that I had met an old woman who healed me, saved me from paralysis, by psycho-spiritual healing. I was playing the flute already, and had enrolled for my masters. We were doing inner intuitive dancing, but there was terrible pain in my back that I thought would paralyze me. Talking with this woman, she was known as Mother Earth, Philippines. She was my mother when I was in the city. Whenever I was tired, I would go and ask for space to sleep with her in her huge bed. She is an arts patron. She asked me what I wanted to do, and I said, “I want to play a significant role in the history of our country”. As soon as I said that, the cold force in my spinal column just went out of my head, there was warmth and the pain went away. With flow, being focused, being creative, being mindful of my surroundings, and experiencing other ways of healing because of the flute, we kept moving until we came back to Sagada because it was expensive to live in the city. I wanted my children to come back, grounded to our ancestral roots. I was then more ready to face my relatives who were very willing to help.

Coming back to the community, I met these five old folks, two old women, and one was a weaver. She is my weaving teacher now. They were preparing concoctions, like magic potions of the witches, but actually scientific concoctions for organic farming inputs. Then, when I was traveling in Manilla, I was meeting advocates of organic farming and had all these spiritual experiences. I got curious, I connected with them and we formed the local organic group.

It was also my healing process to come back as a voluntary organizer with the organic farming advocacy.

There are rituals and ceremonies in our Indigenous community. I brought my kids, who are trying to get back that sense of wanting to reconnect, and to get back on the ground. The moment when I heard my husband was dead, it was like I flew up a few inches above the ground. That was the space that we had to remain in because coming down would be too heart-breaking. I think that space is where the music of the flute also brings people, because I play the flute for everybody. If I like it, and if somebody says it is good, it must be good.

Amidst all these bloody and terrible stories, we still are able to feel and sense what’s beautiful from within and able to share it around us. That’s connecting me with you, and a lot more.

Laureline: Thank you for sharing this story. I can confirm that when you play the flute it moves people, it moves me. We have played it online twice already, and each time I have had people coming back to me saying, “wow, you know, Dom-an talks about sacredness, but when she plays the flute, I feel it”. That is a really rare, unique gift that I want to acknowledge, and I also wish to thank you for sharing this gift.

The question I would like to ask you as a follow up, is how you see the contribution of your art in bringing us back to Earth? As you said, your music is about connecting us back to sacredness and to beauty, which to me are essential when we work on the climate crisis and the ecological crisis, and are not talked about enough. How do sacredness, beauty and the earth connect?

You also mentioned, through the story of your life and work, the importance of healing. I think many of us are engaged in different healing processes at different levels. How does your music relate to healing?

Dom-an: The flute is a wind instrument, it is bamboo so plant-based, and it is spirit. We have to also reconnect to the ground, which is why I chose food and farming as the next manifestation of that healing that we are talking about. I can play the flute forever, it does not drain me.

We have to balance the spirit, the ground and earth, by combining. That is why it is boring to be just playing the flute, if we do not also see our flowers blooming: flowers in our hearts, flowers in our thoughts, the literal flowers around us.

That is why I am also engaged in a project amongst solo parents in the heart of the town here in Sagada. It is a tourist town, trying to wake up from the pandemic and all these lockdowns. We are doing landscaping and a flower garden for the solo parents. It is complex with all the different personalities who come together. I use the flute to chant, to bring people to a certain level of vibration, so that we can understand each other. Otherwise, one is so worried about the next food on the table, one is worried about the coming customers, so much noise. We have to create that silent fine circle of space for listening, because that is the space that connects heaven and earth. Playing the flute, there is a very subtle trick so that the music just flows. You cannot do it forcefully, you cannot enjoy it if it is really mental. It has to come from within, it has to come from that spirit of silence, it has to come to the ground, and take roots so that it goes around. Otherwise, it is consumerist from the product of the earth, consumerist from spiritual energies and it does not make sense. It has to find that balance, the fulcrum of spirit and physical existence, divine intelligence, ancestral and earthly wisdom. In that space of silence, the heart of gold is in the middle. We are not going to steal that heart of gold otherwise the balance disappears. That connects landscape with re-storying.

Laureline: As you were talking about balance, I also feel that when I do too much work which is only about the arts, something is missing in terms of being connected to the ground. That is why we also have different projects. Ecosystem restoration, permaculture, and organic agriculture are very important to our work, and happen through collaboration. When we are not in close contact with those collaborators who work the earth, we are losing context and balance.

My next question is whether you were thinking about the transmission, the passing over of the tradition, or the practice with other generations or other people. If there was something you were doing with that idea in mind, teaching the skills that you have, as a legacy and as part of your Indigenous culture.

Dom-an: I have been teaching how to play the bamboo nose-flute and weaving. I am learning and at the same time encouraging the weavers, because I know there is just so much disconnect now. We can teach the techniques of planting, painting, and playing the bamboo nose-flute; but we miss the core values. That is why it is very easy to corrupt, and to get corrupted. I teach the tangible forms, I do my own research, encouraging expressions in visual forms including the garden, landscaping and symbols. Meanwhile, it is important to connect it with the intangible values, otherwise, there is no point. It hurts to teach young people if when they get the skills, they think they are so good already. The ego is very easy to play with, so it is important to teach humility and that they can always fall and come back to themselves. My mentor Mother Earth said, you can always make mistakes. But, from those mistakes, you learn a lot.

I write concept papers to advocate and encourage people to set up art centers, and organize art festivals. Many times I help others and get kicked out of the circles. I am learning not to be edged away, especially if these are really crucial. Like this heart of town flower project, we reinvest energy, I am learning how to do that. The bamboo nose-flute music is for free, the breath is for free, so if it helps somebody, why not? If it helps somebody remember the value of life rather than jumping over the cliff, let me play and let them call me crazy.

I also make many mistakes. I am very much embedded in the community. That is what I am learning in the community, it is a lot of diverse levels of maturity, curiosity and opinions. I have to learn to protect myself, but not to the point of apathy.

Laureline: That is a fine balance when you do social work, right? To be sure that you’re still keeping some energy for yourself.

I am also curious because you mentioned that you can know the techniques, but if you do not know the value, in a way it does not work. Talking from the European perspective, we have had this huge feeling of disconnection in many ways for a long time. We are maybe the epitome of disconnection, of not feeling part of nature. Many kids have not even grown up knowing nature in urban areas. Do you think we can foster reconnection for people in other places by sharing arts? Or are there some practices that people in Europe could learn from, from what you are doing? For instance, trying to reconnect themselves to values that have been lost a very long time ago in our culture. Maybe as an Indigenous woman those values and teachings are stronger, more present, and closer?

Dom-an: It does not make much sense for us when people like you say you are disconnected with nature. You have a lot of nature. Yet despite that gap, fully empathizing and understanding. The thing is that we journey together, we share the stories without really making each other guilty about anything. I was in Sweden, when I was twenty-two, and there was this huge divide over the ‘First World’ and the ‘Third World’, where we come from. We were supposed to live as a community together. If we were focusing on the differences and the wealth of the other, and what is not with the other: we would be missing a lot of things in that present relationship that we were shaping. So, yes, it’s important to have this conversation mindful of the differences. But it is also very important to communicate these pains and difficulties without judgment, without that sense of having to defend ourselves. “I feel guilty because I have more, and you have less, and I have less”. To create this space of conversation, I think what is important is that we get to talk together, we get to reach out to the soul and heart connections. I think it is the same level that everybody is looking for, whether you are from the First World or from the Third World. I was sitting with a politician, a soldier who some say was cold-hearted, and a human rights lawyer. We were all saying, we have to connect, and we have to feel that connection first in our hearts and souls. We have to learn and relearn to trust each other. Then, connections and order comes in, and we agree to do things that we would like to do together. We disagree, because we disagree, not because we want to fight each other.

Connecting with nature will make us feel like that space of the flute beyond the color, beyond the age, beyond the differences that we have been programmed to think about. We know it gets boring if you just sit there with the bliss, the oneness with the ants, the dragonflies and the rain. It is still very important to have these precious moments to reconnect. I think our role is to help each other rediscover, wherever we are.

It is why for me, I would not know how the flute touched you, I would not know how my words touched you or how you find meaning in it. Just as the author of a book that I read is not really connected with the results. It is really important to keep creating these spaces, especially this time.

We do not know what will happen. There is an emergency and there is talk that 50% of the humans on earth will vanish. Well, we are not yet disappearing.

We have today, and tomorrow and the next day to live, and these values of being grateful for all life, one day at a time. We find many practical things, and all this art. We can pair them with positive values that will give people hope, the capacity to dream, and the inspiration to take action as they dream.

Laureline: No doubt that we are still here, we are still working together, we are still having these conversations. Do you want to tell us what your dream for the future is?

Dom-an: My dream of the future is uncertain.

I dream: I will be able to speak up with freedom; I will be able to live up to at least sixty and continue what I am doing; I will be able to see my children grow happily beyond the trauma, pain, loss [and all the other children also going through loss, pain and doubts]; I dream of seeing 1001 flowers bloom in the heart of Sagada; I wish for organic farming to become mainstream.

Very pragmatic dreams.

Laureline: Thanks a lot for sharing the dreams. Would you like to add anything before we close, a message you would like to share?

Dom-an: Would you like me to play the flute?

Laureline: I will never say no to that.

Dom-an: This one is very fine, the designs are patterned with nature. It is more the traditional natural sound.

[plays flute]

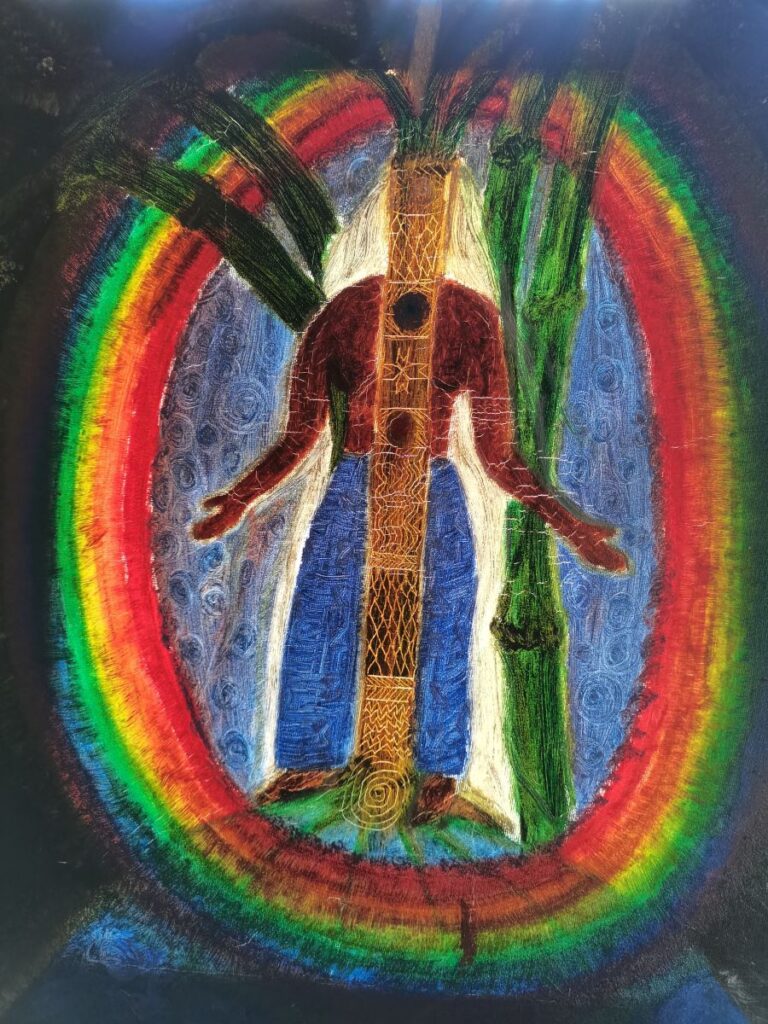

That is the dream that I am weaving. It allows people to see the colors of the tapestry. Despite all the loss and despite all the pain, we do not lose the capacity to see the colors of the earth.

The children will always have the capacity to dream, and our responsibility as adults is to help them realize their dreams. The tapestry is also about unity, uniting and diversity: the colors of life. The dance of being able to move, not being immobilized and paralyzed, and children playing.

Imagine sitting down and listening to children’s laughter, flutes and harps instead of bombs and news about Ukraine and Russia. Seeing thousands of flowers blooming. Yes, our dreams are not that far apart.

Laureline: I would love to be in that world. That is a wonderful dream. Thank you so much for the story, the dreams, the flute playing, it was beautiful. I feel extremely grateful.

Dom-an: Thank you so much Laureline.

My ancestral name is Dom-an Macagne. I belong to the Kankanaey Indigenous peoples living west of the Chico River in Sagada, Mountain Province Cordillera, Philippines. My Christian name is Florence Macagne. I am a bamboo nose-flute player and organic farming enthusiast. I am a widow, and mother of three daughters. I studied a Bachelor of Science in Medical Technology but have immersed myself in community development work since I was 18 years old.

I am currently studying Indigenous mental health concepts and practices in my Masters of Science in Asian Health Practice. I am co-founder of Kasiyana Peace and Healing Initiatives, with a current focus on: sustainable agriculture, children and youth empowerment, regenerative cultural arts and good governance.