Renuka Ramanujam spoke to One Resilient Earth as part of the Re-storying Landscapes in a Changing Climate project. She calls for the powerful force that can be unlocked by bringing art together with action in different domains, fostering the resilient relationships we would like to build with the planet and each other.

Ella: Renuka, how would you describe the practice that you have today?

Renuka: The easiest way to describe my practice, because it encompasses a couple of different mediums and matters, is that it is a reflection of the world I would like to build. Stories and narratives are really important. All of my practice leads back to this theme of our relationships with the planet and to each other.

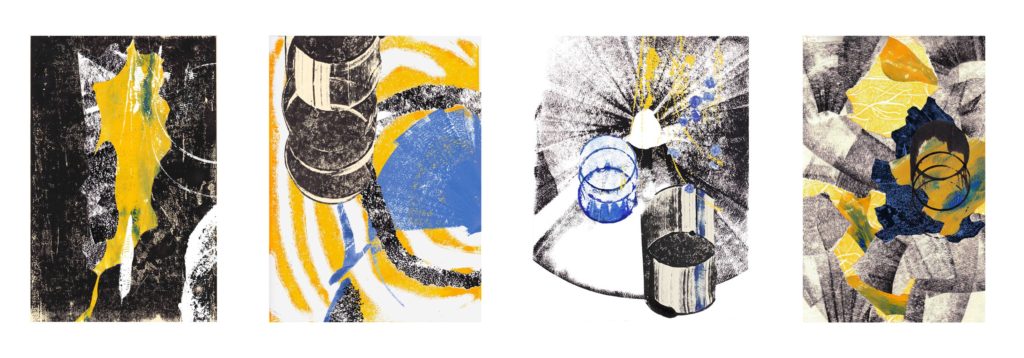

Ever since I was a child, I have been interested in the ways that we used to live and the mythology of past generations. Those stories had lessons enshrouded in them in a way that feels warm, comforting, tried, tested, and trusted. They have these feelings that are intangible in them. I like the idea of being able to make the intangible into visuals, through metaphors or symbols, primarily through my printmaking practice. It is my medium of choice, maybe because I studied textiles. It feels natural because there is something tactile about printmaking, with the impressions and the marks. These connections, metaphors and symbols could be about reckoning with our anthropocentric perspective of where we fit in, in the natural world. Or, realizing how colonialism has impacted certain parts of our culture, food, and identity. Usually, I tend to focus on abstract textures or materials so that viewers have a chance to impart their own emotions or memories onto them as well.

It is interesting to see how the practice has developed. When I was young, I used to be inclined toward this bohemian aesthetic in the ways that people used to live. I was naturally drawn towards nature and wanting to explore that. As I have gotten older, my knowledge of things like the climate crisis has shaped that perspective and added vocabulary. I have been able to channel that into something more refined and positive.

Ella: You mention other’s emotions in engaging with the material of your work, and your knowledge of the climate crisis shaping your perspective. Would you like to say more about how your own feelings about the climate and ecological crises impact your practice?

Renuka: As I understood more about the climate crisis, and tied it to the way of living I was drawn to as a kid, I was able to deepen my perspective. It has taken away some of the more fantastical and aesthetic elements I have liked in the past, and made it grounded in fact and emotion. I am still the same person, but that attraction to nature has more of a specific edge to it now. It has also given me a new sense of consciousness, a whole practicality that has been added to the making process. Is what I am making strictly necessary? How do I make it? Is it contributing anything positive? What potential impact does it have?

Ella: In this project we are talking a lot about resilience, would you like to say something about the ways that your practice impacts resilience for you and others?

Renuka: For me, I think

it’s important to put stuff out there that can help educate and raise awareness without disheartening too much. To empower people to be able to say, I can do something about this.

I think there is a fine line with that responsibility. Sometimes, you feel like these topics are so huge that you can be biting off more than you can chew. It can be weighty to take on something like that, and not feel the stress and pressure of it yourself. One of the problems we have within the world is over-consumption, and while an artwork can make people aware of it, what you are putting out may not specifically be utilized to reduce plastic pollution. But, you can inhibit your own creative practices with those thoughts and questions sometimes, and stop yourself from being able to have that creative flow. Part of the reason for being an artist is to be able to evoke emotion and share that with people. Those moments can be the most powerful ones that people connect with. So, I think it is important to be able to free yourself from those shackles, while there is a responsibility as somebody who is making to be very considerate about it.

Ella: Bringing together both that critical reflection and creative imagination needed for change, do you feel your practice has grown and expanded imagination and creativity in ways that make you or others feel better equipped to address the climate crisis?

Renuka: I cannot stress enough how important dreamlike narratives and stories are. Even if you do not necessarily come out with a physical output that second, that imagination can spurn other ideas.

My practices also brought me into contact with other people through this process of collaboration, dreaming and resourcing. They have helped me gain more insight and knowledge into the nuances of the climate crisis. This is so important and helps structure my practices.

I have both an artistic and a design side. I use the artistic side to learn, feel and understand how the climate crisis is felt by people and is driving them. It has been an incredibly helpful tool to develop an emotional vocabulary that can be channelled into something else, the practical design side.

I have this biotech start-up, that is creating a material out of onion skins. Now, I am thinking more in circular systems than I was previously, and it has helped me ask questions when I am doing things in daily life, when I am traveling or recycling. It has expanded my practice and allowed me to constantly and increasingly think out of the box, and for that I am really grateful.

Ella: Could you tell us more about the way your practice contributes to regeneration towards increased health, wellbeing and life in individuals, communities, and ecosystems?

Renuka: A part of my practice is being able to synthesize information into outputs that people find unexpected, and makes them stop and think. There is an element of teaching and helping share knowledge. I was working with mycelium, the roots of mushrooms, to create this insulation material in a design-focused project. I got the chance to speak to other designers working with it, to learn from them and how they were utilizing it. Part of the process of working with this material is that most people dry it out in the end, so that it is more usable for us. If you leave it wet, it is kind of mushy and icky, people do not like it. But, actually some of the properties are more potent when it is not dead, because alive it is doing its thing. I was saying, “it’s a really great material” and this designer was saying to me, “yeah, but I look at it like a design partner, now we’re working on this together. It is growing and enabling us to work. Then at the end I have to kill my design partner.” I thought that it was a really beautiful way of putting it.

We have essentially said, “I am going to take this thing and use it for my gain, even though it has done most of the work”.

It flipped the switch on the way that I was thinking, and I wondered how to express this dissonance that I am experiencing. When I started working with it more extensively, I thought, “wow, this is a really incredible kingdom”. We have been running around thinking we are top of the chain in intelligence. Learning more and more about fungi, it is incredibly intelligent in ways that we cannot begin to imagine. Through that experience, I decided to create a series of artworks comparing humans and mycelium.

A human marker of progress is revolution. I was comparing that with the way that mycelium takes over its host substrate, using abstract visuals that could reflect a human revolution. Starting with a festering of emotions, and the mycelium starting to find a damp wet spot, there was this idea of things growing underneath all the way to taking over the log as a revolution. They were done in such a way that people were saying to me, “I had never thought of that parallel, but seeing this, I have been able to question that”. I like that aspect of the practice, in being able to bring these topics up and make people think in different ways.

I also lecture and teach, which I feel is a really strong way of building resilience, because you are empowering other people to approach a problem. They are probably going to approach it in a different way than you are, so you are putting more hands on deck with a higher rate of success in solving the problem.

Another way the practice contributes to wellbeing and ecosystems, is empowering people to understand the materials around them.

I run a lot of workshops with natural dyes and screen printing within the textile field. Textiles are important to us, we are constantly surrounded by them, and maybe blasé about how much they impact our lives, in good and bad ways. I hope to increase understanding and respect by encouraging people to take a closer look at how things are made, and in using the abundance that is around us in natural materials. If they feel like they can do more to mend by themselves, we can reduce reliance on larger structures that may be causing us damage.

Ella: Do you want to expand further with examples of where you are working with communities, local initiatives, co-creating and local projects to contribute towards a more climate resilient and regenerative future?

Renuka: I think that contributing towards a more climate resilient and regenerative future is very place-dependent. You can always create your own community, but being in specific spaces, you realize you are more likely to be able to build those communities. About two years ago, I moved to the Highlands in Scotland from London. Suddenly, the focus on community has become so much stronger. There is this element of taking care of each other that can be absent in the big city. Our locations can impact our ability and ease of access to these opportunities to create spaces. While being here, I have had such an eye opening experience with community work.

Especially with things going on in the world right now, to be able to take care of one another, help each other out, and provide for one another is so important. Also, it creates an opportunity for more harmony, by being able to understand each other within your small area and say: “this is what we all want, this is what we need.”

One example is: I have been involved with a local marine science-inspired textile brand. They create high-end luxury accessories, mostly scarves, that are inspired by the sea. They were seeing topics that were coming up in marine biology, microplastics being one of them. They wanted to create an outreach program for that, for the next generation. I was brought in as a workshop artist there, and we worked with some children from a local primary school. They were able to tour around the marine science labs that were next to the textile studio, because it is affiliated with the Marine Science University, and understand what was going on with microplastics. They could see them under a microscope, and look at the robots that are routinely sent out to monitor and take photographs. It was really insightful. Afterwards, we all went on a beach clean-up to look for evidence of this washing up on the shore, of which we found lots. We had a printmaking workshop where we discussed how this made them feel for the future: what their thoughts were and the solutions that they felt they could create. We were trying to use art and design as a channel to express all of this. It was incredible seeing what the children came up with, and heart-breaking. They were only nine or ten, and were already aware of the fact that the future is not looking that bright. Through this workshop, they were talking about coral bleaching, and concepts that I had not heard of until I was in my late teens. It was fascinating to see the next generation adapt and express themselves this way.

Secondly, I have been working with Dig It! Scotland, an archaeology association which covers a lot of historic sites. One of their sites, Swan Grove on Orkney, is facing severe coastal erosion. The site is an Iron Age roundhouse, and dates back to the first century A.D. It takes time to excavate and really understand what was going on there, and for two years they were not not able to access the site because of Covid-19. In that time, they have seen an alarming 30 centimetres of stone submerged. At that rate of coastal erosion, they do not know how much longer they have, and what could potentially be lost. So, I worked together with Dig It! Scotland on a campaign to create visual imagery, and communicate the issue to start conversations about what is happening. To be able to understand more about the artefacts and what is at stake was really rewarding. It ties back to loving to know how we used to live and not wanting to lose that window into the past.

There is also a really beautiful local initiative here, called the Seaweed Gardens. We were encouraging local, particularly coastal gardens and coastal communities, to utilize resources and foster stewardship. We took the ancient practice of using seaweed as fertilizer, where you ferment the seaweed, and tried a variety of experiments to see which ones work best. We used it at our local community gardens to grow different crops, and created a green zine to distribute to the community gardens. Through a series of events to foster this sense of stewardship, we invited people to discuss how to use and not abuse seaweed with the intention of giving back, and how it felt as people living in coastal communities. There have been a lot of great conversations and outcomes from that project, and we have been in touch with many other community gardens around Scotland.

Lastly, I have done a project recently with the National Archives and the V&A. It is about community and getting people to understand their heritage better, especially in a world where that is easily diluted. The National Archives had a chance to show artefacts outside of the archives setting for more public engagement, which is not something that happens very often. There is an idea that these items in the archives are meant to be looked at in very specific contexts, which are not easily accessible to the public. That was something that we were trying to break. These artefacts were from European ships that were plundering or ‘prize taking’ those they deemed as enemies, in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Many of the ships were going through Indonesia and China in Asia for the trade of spices and fabrics, known as the East Prize Papers. We were examining a particular specimen, a wallet, from a Dutch merchant. It contained seeds from different countries, some of which are now even extinct. It also held fabric samples, and we were focusing on how they were made. The Chinese and Indonesian silks are exquisite, and considered UNESCO heritage for the way that they were made back in the day, now that this has been replaced with mechanized looms. We were exploring the natural dyes and techniques that were used, and getting a better understanding of society and culture back then. We held workshops in both London and Manchester with children from Indonesian and Chinese community centres within the UK, showing people the time, value, techniques and traditions in these textiles. Some of these children had never seen an embroidery hoop or loom, and here they were able to try for themselves a small sample of how these things were made on these pieces of equipment. For them, it was incredible.

My thinking from the textile perspective was that, if they can understand how long it takes, they may value that piece of clothing they have for longer and open their eyes to the idea of natural dyes.

That ties back into what I said before about materiality, and getting people to see the value in time and making.

Ella: Thank you for sharing these projects exploring some important climate change issues and resilience themes: microplastics and marine life; the loss and damage of heritage and land; traditional ecological knowledge and practices; supporting communities in their stewardship of nature; and perspectives on value.

Is there more you would like to say about your contribution to repairing climate change-related loss and damage, and promoting climate justice?

Renuka: Apart from looking at the value in materials, and being respectful to the abundance of the natural world around us, there is an academic writing and researching component to my practice that helps inform the artwork that I do.

Writing articles about climate colonialism and loss and damage is part of this work. Who takes the responsibility and where? If you are reading into the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, it gets so heavy. I try to simplify and make those messages as clear as possible for people, so that they can feel a part of this. When I was younger, I was turned off because politics seemed so complicated, which is really sad because it is so important. Seeing things bogged down in long documents and not having an awareness of what has happened in the past have the same effect. It is not helpful for the masses who need to be engaged.

I am reckoning with the onion skins design start-up side, asking, “am I doing something to contribute?” Apart from awareness and evoking emotion, I want a practical solution, because that is what I feel, to a point, is necessary. Being in the textile industry and understanding where the pain points and pressures are, you see where COPs are putting out policies with clear holes, because they don’t have the right people at the table. I have been in an ongoing process consulting all the right people, to ensure that I am making a measured project that can be used around the world. To have a wider impact within local and regional hubs; to create jobs; and transition economies out of plastic pollution through new nature-based solutions. I want to say, I have done my homework and I am really trying to impact. I do not want to just think about the UK and the Western world, I want to consider what happened to the places where often voices are silenced or purposefully not listened to. I think that creating this practical solution with them in mind, at the forefront is where I feel my biggest contribution to loss and damage is.

Laureline: Would you also like to tell us more about your work with natural dyes? It feels like a very concrete way of relating to places where people are, and as an impactful nature-based solution.

Renuka: I was working mostly in screen printing at university. All the ink that we were using, we put them in these massive blue tanks when we were done. I do not know where they were disposed of. When you looked into this chemical, multi-colour bright sludge of things, it felt weird not knowing what was going to happen with it. We had done some natural dyeing, so I thought of screen printing with natural dyes. Natural dyes are amazing, but I can understand why they are not used in a more commercial sense because they are not made for commercial use. This is quite beautiful, because you are giving yourself this philosophy of letting the dye do its own unique thing, you are working with it, you cannot force it. That is where I was attracted to making these one-off things that really meant something.

I assisted a natural dyer, who was able to forage tree bark, through different points of the year. The colors change depending on the seasons, so it was a story of the tree. I thought that these natural dyes created such a connection to the plants and where they are at. It is a living dye in a way. I try to use dyes that are local because it is also a way of connecting to what is around you, as opposed to dying with indigo shipped from India halfway across the world. Another interesting component of natural dyes is the opportunity to really understand its provenance, which is not the case with synthetic dyes at all. I never have any expectations when I use natural dyes, because it is wise not to. At the same time, it means that every piece is its own story. At the moment we have a small dye garden locally that I sometimes assist with. We are growing dye plants here that are local to the UK. It is a wonderful way to understand the season, because you notice when things are in bloom and what is available when. That also goes for food, it extends into this deeper conversation on working with nature and what is there.

Laureline: Before we close, do you have anything else you would like to share? A message that you would like to spread in relation to your work?

Renuka: Reflecting back on the project through working with other artists in the UK and the Philippines, I think it will be interesting to see how different locations and experiences make such a difference to our perspectives on these sorts of things.

Art is so important for starting conversations. I do not think we should negate the impact of the arts in communicating, inspiring and empowering. I think what needs to happen is linking art with actions as well. Whether that is through bringing it together with science, archaeology, or with other areas. That is when it will be a really, truly powerful force.

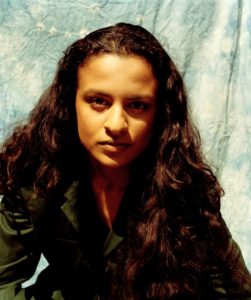

Renuka Ramanujam is a printmaking artist and material/textile designer. She is interested in how materials play a large role in our lives, and the creation of regenerative design systems. She is currently based in Oban, where the Highlands stunning scenery and wildlife nourish her practice. Her startup HUID, focuses on utilizing onion waste to create a material solution to single use plastic packaging.