Emily Joy is a socially and environmentally engaged artist, participating in the Re-storying Landscapes in a Changing Climate project. Emily shares with the One Resilient Earth team how she strives to bridge the gaps between people with community art, while exploring grief as a catalyst for care in the climate crisis.

Ella Maby: Emily, what is the story behind the practice that you have today?

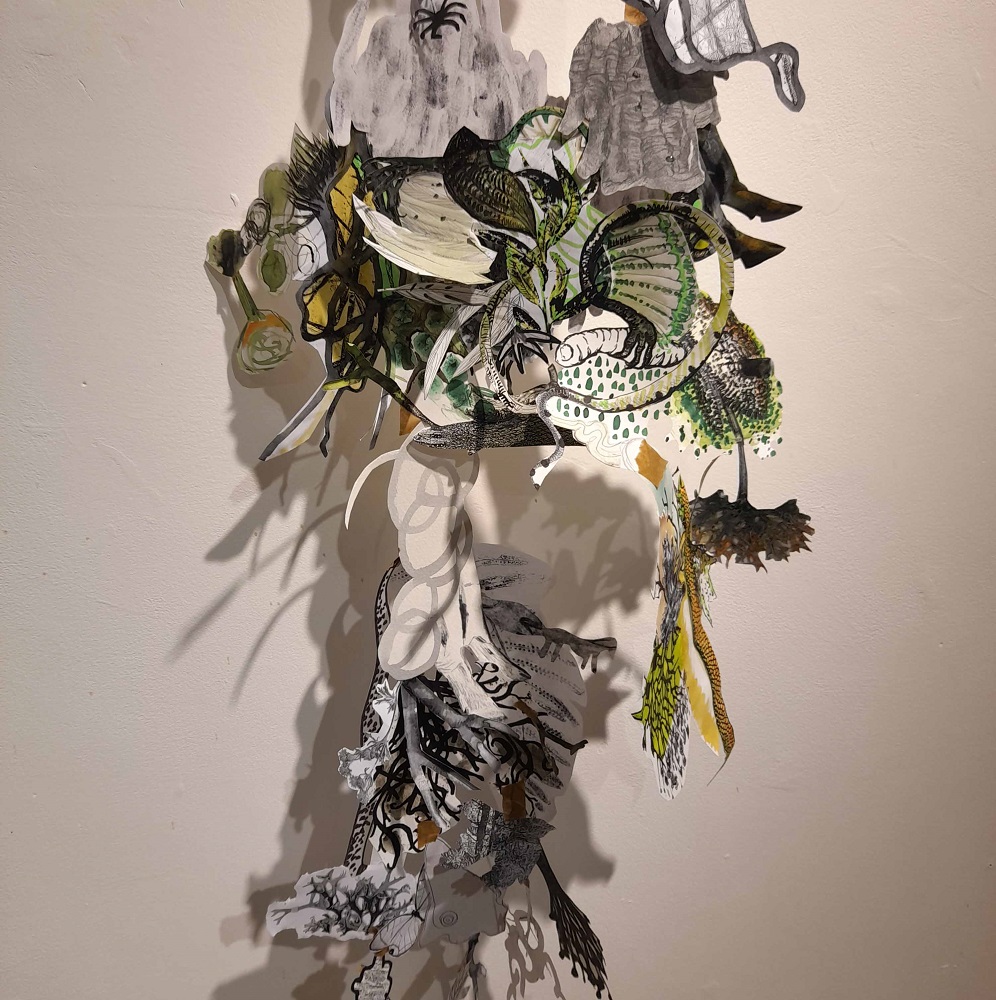

Emily Joy: I’m currently describing what I do as socially and environmentally engaged work. I’m a trained sculptor, ceramicist, and I make a lot of installation work. But at the moment, I’m really doing collaborative work with people.

About 15 to 20 years ago, when I was studying, I started working with ideas of memory and loss, from a very personal loss I had experienced. Whilst I was researching memory and grief and all of the psychological processes that are bound up in those emotional states, I started to read and explore a little bit more in my practice how we create a sense of self as an individual. Then within the last ten years or so, that’s got to the point where I realised that

an individual is not merely formed: you are created by the networks and the people that create you. Our sense of who we are is always in flux and changing. As a result, that relationship between our sense of identity as an individual, the broader community and connections with family, and what happens when we experience a personal loss started to become really important in my practice.

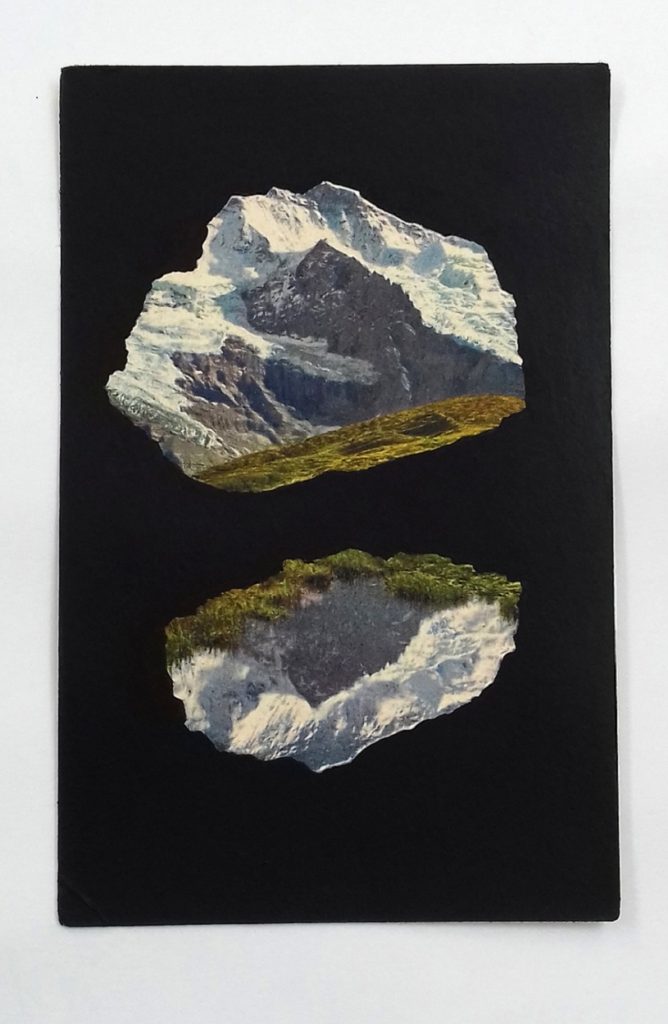

From a very personal story concerning my father (who had travelled and I found some of the things that he had left packed away) and that experience of losing him, I started to explore how we can really connect to other people through shared workspaces, sharing stories and sharing experiences. I was pulling on other people’s emotional responses to some of the objects that my father had left that I was using in my practice, opening out these incomplete memories, and exploring a very personal part of myself linked to him by asking other people to help me complete the memories. Some of those objects, images, slides and photographs that he left were to do with a journey he made 50 years ago to the Swiss Alps. At that point, the personal and the collaborative work that I was doing started to solidify. The environmental impacts that I was seeing through these photographs that he had left started to gently feed into my practice. I was looking at photographs that he’d taken 50 years ago, and by looking at Google Earth doing a virtual retracing of his journey, noticing how very different the environment was. Not only the things that we’re more familiar with, like a glacial melt; but also the things that surprised me a little bit, like the growth of trees, vegetation and these incredibly lush landscapes that had sprung up.

So, where I am now is this combination of opening up something very personal to do with loss, and then looking at whether there are parallels with the experience of climate change.

European experiences of glacial melt, material loss, ecosystem and economic loss, all of those different issues tie together. Whether that very deep sense of personal loss, all those emotions and that level of grief can also be felt for an environment or for something that’s not a human. The collaborative work that I’ve been doing has to do with: sharing a viewpoint, workspace, environment, or task; to see if we can bridge that gap between the individual and the other; to feel responsibility and care in a shared space; and to explore whether we can have a really deep sense of empathy for the other than human, and for people who are deeply affected by similar climate related issues that may live in a very different culture or are not be particularly familiar to us. So really pushing and exploring those boundaries.

Ella Maby: Thank you so much for introducing everything, you covered a lot of the themes that we’re going to talk about.

You talked about connecting with feeling loss and empathy. How do your emotions or feelings about climate and ecological crises impact your practice? Could you say some more about that?

Emily Joy: Thematically it’s central. But when looking at it from a slightly different perspective, how do the emotions day to day physically and practically impact what I do? I talk a lot with the other artists I share my studio with about this:

how do we carry those emotions? The sense of care, guilt, and grief – especially if our practice is explicitly about climate change.

I’m reading articles every day about what glaciers are threatened, and what proposals are in place to protect glaciers that will protect water sources for people. I suppose it’s important to allow those emotions to be felt, and find a way of doing something useful with those emotions.

I was thinking, to a certain point in my life, how separate my activism has been from my practice. Until about six to eight years ago, they were very distinct. I did a lot of protesting, I was involved in transition groups, I was a member of the Green Party. I didn’t see it as something that was particularly to do with my practice, the two hadn’t become integrated at all. I guess things just evolved. I haven’t really analysed why that’s changed, other than I’ve explicitly started working with climate change because of this collection of images that I found and started using from my father. I think it feels very healthy to have that integration now. It is quite hard sometimes, but it also feels quite purposeful and that leads me onto a slightly different area. In the research I’ve been doing for the last two years, I’ve been talking to a lot of artists who are making work in response to climate change and ecological loss.

I’ve heard again and again from artists and from creative practitioners that what they’re doing isn’t telling anybody what to do, or having a very explicit or superficial message. It’s much more to do with drawing out emotional and psychological elements.

So, when I say it feels quite purposeful having all of those interests, passions and all of those things integrated with my practice: I don’t mean purposeful in a way that it’s dogmatic, it just feels that I’m really starting to draw out some things I’m interested in, that seem to be very important to communicate at the moment.

Ella Maby: It’s really good to hear you delve deeper into that learning. Linked to how you were talking about purposefulness, in what ways do you think this practice impacts your ability to bounce forward?

Emily Joy: There are days when I come into the studio and I sit down with the other artists that share the space. We’ve worked together for 15 years, we’ve seen our work develop, we’ve seen each other have families and go through very happy times and difficult times: we’re very, very close. There are days when we come in and just say: what is going on? What do we do? Why are we doing this? Why are we still here? We can barely afford our studio, in terms of sustainability, we’re struggling so much just to keep going.

We come back to this idea that it’s really radical and important to be doing art, whether or not we can see an impact with what we’re doing, we just need to keep doing it. Just the fact that we are not conforming, that we are stepping out of the norm; that we are trying to pull out deeper threads, cultivate creative connections and really focus on what we see as the important things.

The fact that we’re just trying to do that, and having that network of people around me as part of my practice is what keeps me going forward. Working collaboratively, it’s the feedback you get when you’re working with other people and you make a connection. You have a shared impact on each other and you get that lovely feeling of co-creating or stepping out of your individuality into a shared space. The potential within that, even if it happens just once in a day or week: if you get that connection and support, that for me, feeds me for weeks. I live in an incredibly creative, very politically active town: there’s an amazing, really supportive network. So, as an individual, I’m very lucky to have that and to have a lot of other people around me to keep going.

Laureline Simon: Would you say that this community is really essential for this resilience that you’re talking about? How do you see the link between community and resilience in your practice?

Emily Joy: I’ve been working very mindfully with the community in Stroud for ten or twelve years, maybe more, through my teaching and then through workshops and community events. Alison and I also do Periscope events, which are these non-hierarchical immersive spaces. Through all of those different aspects, it’s all of those different ways of connecting to people: what we come back to is the connections and a strong sense of community. My involvement with Transition was all about creating a resilient, strong community: because there is a sense that we will need that more and more, and I think that’s not even in question.

We need to build connections on a really practical level so we know who to go to for practical things. On an emotional level, we need to know that we’re held within the community and that we’re not doing it all on our own, that we can share with somebody else.

I don’t know how that extends beyond the local community, I haven’t got there yet. I’m so excited about the Restorying project, because I feel that my experience has very much to do with this tight-knit community.

I would love to ask you a question, and it might be a question that you don’t answer: shall we go into communities assuming that people want to be connected? It’s the question that I ask myself with every collaborative project that I invite people to interact with: “do people really want this?” Maybe it’s not even a question, it’s just remaining in a state of humility. It’s not assuming that a community is necessarily asking for resilience or those connections, but offering it and seeing what happens.

Laureline Simon: It’s a question I also ask myself. Whether I work with local communities or with transnational communities that we’re trying to create at One Resilient Earth by having series of workshops and a community platform where people can connect and gather. I feel that somehow we all want community, but we don’t necessarily know what it is. As if we are unsure what it entails, and how much we’ll be tied to it and what we’re supposed to do in it.

I also see value in creating very transitory communities. Any online gathering of people trying to support each other is a community. Some of them will last, some may not last, they may evolve over time, we don’t really know which ones are going to persist as communities. I think that’s what keeps me going in running this organization and creating all those different communities.

Ella Maby: Perhaps the forces of individualism that we’ve experienced for a long time mean that it’s a re-learning of community. But, then, there’s so much more opportunity for transitory communities online and across the world. So, connecting is a different terrain, isn’t it?

Going back to our questions, Emily, do you feel your practice contributes to regeneration: in the sense of increased health, well-being in life and individuals, communities and ecosystems?

Emily Joy: It’s really interesting because what I was thinking, Laureline, when you were talking about the transitory networks and communities is that actually quantifying the impact of those is really hard. Most of the work I do, the connection, and the positive impact is felt on a really personal level that can’t be held, shown or evidenced. I don’t know whether I’m slightly taking that question not in the way that it was meant. But, so much work that I’ve done in the past has been workshops to encourage communities or groups to engage with nature or to improve mental health through creative participation. Although I see the value in that, absolutely, I also feel really sad that we’re prescribing those things. I’m wary of trying to evidence anything I do in relation to communities and networks. Undoubtedly what I do contributes to the regeneration of communities; but I couldn’t tell you how, or how much or even who is benefiting from that. But of course it does. I’m making connections. That’s what my practice is all about. I think when you work in that sort of way, when you step away from the council led or the funded outcome led criteria. You do have a bit of freedom as an individual practitioner to just try something out, those outcomes dissipate out into community; but you have to trust that they are having a really positive impact and there’s always a lot of word of mouth.

Because of where I’m living and how I’m living, I’m not dealing with climate impacts at the frontine. I’m dealing with a slightly more insidious lack of empathy, of a feeling of being completely demotivated.

This is what I’m seeing in participants with a lot of creative events and collaborative pieces I do with the public. A sense of complete loss of the people’s trust in their own imagination. I’m not working with the immediacy of a climate crisis, I’m working more on the psychological levels of, “why are we disengaging? How can I re-engage you on an emotional level that feels okay and safe, or maybe in a way that doesn’t feel safe?”

I think that’s where my skills are and where my passion is. Digging into the deeper reasons behind behavioural responses to climate change, and responses to climate news. On that level, any engagement that I have with the public in this community will have a positive impact, because people will be imagining and joining me, meeting me somewhere.

Even if it’s a difficult conversation or a challenging conversation, there is something happening, there is something being faced or spoken about.

Ella Maby: One of the themes you mentioned was imagination a few times. How do you feel your practice expanded your imagination, or has grown your creativity in ways that make you feel better equipped to address the climate crisis? Maybe that can be linked with what you’re describing around community work as well, the place of imagination in all of this?

Emily Joy: Yes, definitely. From what I’ve experienced, there has been an incredible change in how I teach. I’ve had a process of unlearning my own teaching methodologies, really questioning learning and hierarchies within learning and education, and how we communicate to other people, how we invite people into spaces. I think I touched on it before with this process of opening up a personal piece of source material, or a personal memory or emotion to others. It suddenly expands not just your sense of self, and the possibilities within your own memories and your own experiences, how you go forward. But, in terms of your imagination when you’re working with a group of other people: the sparking off of other people, the things you can learn, the methodologies you can learn… Having a collaborative practice imaginatively just expands everything so much. I feel like a lot of my work is going towards a really collaborative approach. I do a lot of participatory work, where I invite people to do something with me. Collaboration for me is something a bit more than that, it’s where I really open up everything about my practice and allow someone else to come into that and meet me on a level of equal holding of space.

There’s a huge amount of unlearning that has to go on with that in terms of ego, power and control. I find that really exciting because I think for me that is where imagination can come from: when you’re meeting somebody else somewhere in the middle; sharing their experiences and your experiences, and imagining something that you wouldn’t be able to imagine before. This feeds into how we imagine the future, how we imagine something better or more positive.

Laureline Simon: There is something quite fascinating about the sharing of personal experience: you can see how it is touching people sometimes even when you’re doing it. Usually we have absolutely no idea what it’s going to unlock in that person in terms of other memories, imagination, or visions… which makes it impossible to capture with the usual impact assessment. But this is actually the process of transformation happening in real time. You’re opening up something that has to do with imagination and creativity in someone. If we could capture projects’ impacts as, “ people’s eyes were shining brighter”, or, “there was a different vibe in the room”, “everyone started talking a lot”, that would be perfect. We do need new ways of measuring the impacts of those projects, because impact is not linear. Maybe you had an amazing impact on that day, or maybe a few months down the line the impact will happen, differently.

One last point about impact, is that it’s an issue for all climate adaptation projects: you never know if you built the capacity of a population successfully in relation to climate adaptation and resilience unless some extreme weather event happens. But we still have to prepare the best we can. I feel it is something that is inherent to the building of resilience in general, whether it’s climate resilience, or other types of resilience: how are we going to assess in real time if sharing all we have learnt from going through other storms will help people or not?

Emily Joy: It makes me think of a project that I did a few years ago with Alison, as Periscope. We had funding and we were able to pay for an evaluator. We chose her very carefully, she was somebody we knew and works with creative projects. She was really okay with our very nebulous, loose ideas of: “what are we evaluating?” She evaluated very physically, so she looked at where people went within the space, and how long they stayed in a space. There’s really creative ways of seeing where people go, how long, how they map a space, how they understand it, and then where they went afterwards. Yes, criteria for evaluation becomes very different, doesn’t it?

Ella Maby: I suppose what both of you have been mentioning is measuring through embodied responses. Whether that’s mapping physically or emotional inspiration in someone’s eyes. And that’s a big part of this isn’t it, reconnecting with each other, ourselves and our environments.

Emily Joy: This made me think of some other experiences that I’ve had where the connection or the response hasn’t been positive. Where I’ve come up against somebody’s boundaries really strongly, or somebody choosing not to engage because it feels uncomfortable. I try to stay really open to those experiences as well and not write it off as a failure; to see it as something really valuable and interesting to take on.

I think it’s this idea that impact could be at many different levels. It may seem like a negative impact where you’ve challenged somebody or they’ve made you feel uncomfortable. Yet, there’s still that dynamic exchange between two people that is crucial within this conversation we’re having about climate change. The connections between people, and the care between people and places.

Ella Maby: Discomfort and challenging our assumptions are part of the process. Experiencing a full range of feelings, rather than us choosing only those which we like or are the most comfortable.

Emily Joy: Yes, not always making it comfortable. A lot of the work I do with other groups is focused around ideas of conviviality, invitation and how you open a space to everybody, so very democratic spaces. But the work I do individually, although there’s not such a clear divide, is much more to do with challenging and making people feel a bit uncomfortable, and seeing what happens in those spaces.

Laureline Simon: Circling back to what you discussed in the beginning, Emily, loss was very central to your work. If we relate the root of your story to your practice, to this bigger question of loss and damage and climate injustice, how do you feel your own practice addresses this question of loss and damage?

Emily Joy: I’ve been told that some of my practice is too depressing or isn’t cheerful enough. And I think that’s fine. I think we need to be braver at facing the really uncomfortable things, the really not positive things, feel the discomfort. Especially as I’m living in a very privileged position where most of the world around me, most of my culture within the UK is about comfort and about not facing loss; not really thinking about loss, not really thinking about discomfort or damage, pushing those things out and surrounding ourselves with lots of comfortable things and environments. It’s something I think about a lot, how much we explicitly talk about loss and damage when we’re not actually experiencing it, how much we want to go there and what impact it has. XR’s methods have been criticized for being too extreme and too negative. I suppose putting the worst case scenario in big neon lights so that the people can’t not look at it. I understand the criticism of that, of making something maybe too painful to look at, or too uncomfortable to experience. That gut reaction that people can have. But I think it’s really important to face that, Dougald Hine who I’ve been working with, one of the co-founders of the Dark Mountain Project, writes about what artists can do in relation to facing loss, and he talks about it as a way of looking obliquely at something.

A way of looking at something through art that enables you to stay with the horror, the sadness or the despair. It allows you to stay with it so you don’t switch off, as it presents it to you in a way that is slightly abstracted or as a metaphor. You can still look at it and experience it.

But I’m really aware that everything I’m saying now, I’m talking from a privileged position, because I’m not living the reality of it, so it will always be through metaphor and through abstraction.

So how does my practice contribute to repairing climate change related loss and damage? I think my practice doesn’t explicitly do that. I’m really okay with that, I think on a gentler, quieter level, that oblique way of looking, that sideways glance at what’s going on, that’s where I’m operating, because I’m not experiencing it personally.

All I can do is feel empathy, and try to draw out empathy and connections in other people, in the hope that it is a catalyst for care in other areas of people’s lives. That’s where my hope is and where my action is behind my practice.

Ella Maby: Is there more that you’d like to discuss and dive into with us in using your art forms to co-create with communities, local initiatives or local projects towards a more climate resilient, and regenerative future?

Emily Joy: Co-creating is what I’m really excited about. My very small experience with storytelling events has been so transformative for me, and I hope for the people that are involved as well. Just seeing the potential in sharing individual personal stories within a sitting-in circle, within a really safe group; or within a really magical environment where imagination and memory can come to the fore and be shared. That co-creating conversation, storytelling, sharing, sharing very personal experiences, sharing the subjective. Rather than looking for an objective response to something, I think I feel like I’ve gone beyond that, I don’t feel particularly able to work with facts with other people, if that makes sense. I do a lot of research, a lot of reading, including articles about the statistics of climate change. It’s fascinating and horrifying. But, when I talk to other people, other things seem to come out as we sit down and start making together. I recently did this piece with un-threading fabric and we talked about weaving. So much came out in terms of women’s weaving mythologies linked to the environment and linked to weather, linked to loss and taboos. It all spirals around, and you find yourself talking about the bigger things, but without really knowing it. Hearing somebody else’s personal response to it is so exciting. It’s all about co-creating and trying to stay humble.

As an artist, we’re often trained to have egos, to have a personality and style that is very strong, and be able to explain ourselves to know what our work is about. I felt all of that just shedding in the last five to ten years and just not being relevant anymore. I know it’s still there, but I really want to become more open and porous, and learn and listen even more.

The sense of ownership over a practice, I’m even questioning at the moment. I’ve been talking about myself to you. But, I keep thinking about all the other people that have made work with me over the last two weeks, where I’ve been doing this intensive collaborative work: they’re really part of it. I feel like, as artists we’re not really supposed to do that. We’re supposed to still claim ownership over our practice. When you start working collaboratively, you can’t. It’s all about Ali, who I work with, and the 20 or 30 other people that came in last week.

Laureline Simon: That’s a great point. When working on co-creations, it feels that it is a good thing that we no longer know which part is ours. Moving away from the old paradigm where we want to put labels on who owns what. The reflection can also go deeper in terms of what really comes from us and what comes from older generations: what do we really own? When it comes to a technique, to knowledge, where does it come from? It is even more interesting when we encounter Indigenous Peoples’ collective ownership of knowledge, for which our approach to intellectual property rights does not apply. Before accessing or giving access to that knowledge, we need to ask permission from the whole community, including the more-than-human members of this community. Maybe instead of thinking in terms of ownership, we should think in terms of permission more? But we can leave it there for now. Thank you Emily for sharing your story and experience.

Emily Joy: Thank you both so much. Just being part of this conversation was amazing, so, thank you.

Emily Joy is a UK based, socially and environmentally engaged artist making sculpture, installation and performative work. Currently exploring Swiss glacial melt and the associated ecological and social impacts, her practice is centered around participatory work and collaborations that investigate communication and empathy. Her work is also driven by cross-disciplinary collaborations that question hierarchies and assumptions about knowledge and learning.